2030 Policy Endorsement of a Sustainable Future: Implications for Urban Research

by Susan Parnell, Owen Crankshaw & Michele Acuto

1. Introduction

Not since the United Nations was created after the Second World War has there been such a concerted effort to galvanize the global community to act differently and to manage cities and territories better, ‘for people, planet and prosperity’.[1] Unprecedented demographic growth, climate change, unchecked consumption and increased human exposure to natural hazards and other risks have precipitated a shift in the social norms of the international community, making many policy frontiers more receptive to ‘the city’. Several UN agreements now acknowledge the essentially urban character of our common future and set out a ‘2030 sustainable development agenda’, with specified goals that will frame national and local actions. In policy statements across the UN, a coherent view that cities and towns are a non-negotiable feature of the future is gradually emerging, marking out a distinctive new scale of global policy direction and opening significant questions for research.[2] The central concern of this paper is to interrogate what this shift to city-centric global thinking means for urban research and for intellectual leadership in the urban community more generally.

If you would like to contribute a comment to this debate, please email us.

The foundational point is that the foregrounding of cities revises global thinking about sustainable development in ways that go beyond the traditional UN views on human settlements associated with the Habitat Agreements of 1976 and 1996.[3] While the utopian aspirations of the earlier Habitat Agenda have yet to be fully implemented, the bi-decadal opportunity to rework the global policy vision is once more upon us. What sets this cycle of policy making apart is that it is not just the question of what to do in cities that is under debate, but also an additional claim that whatever is done in cities will have repercussions across the global environmental system. The former concern draws on an intellectual tradition of politics, public administration and planning, and the latter on methods and debates associated with the life and natural sciences. One of the problems in mediating these parallel claims is that the overall policy consensus that has been reached is fragile and rests on competing abstractions of ‘the urban’ and its importance in the global system. There is thus a paradox: at exactly the moment that cities have been accepted as pivotal in crafting a sustainable future, the urban community is conflicted about what this actually means, or implies. We argue that this ambiguity makes the working definition of ‘the urban’ a key concern. For the research community the challenges are thus first to agree on what the objects of further analysis might be, then to contemplate what the best institutional mechanisms are for deepening the science policy interface, and finally to ensure that research funding is appropriately focussed to respond to promote innovation and fill knowledge gaps.

Few anticipated the rapid and wholesale urban realignment in global policy discourse that has occurred in recent months.[4] Adjusting to policy ‘success’ means shifting rapidly from always having to make the case for the importance of ‘the urban’ in sustainable development, to spelling out what urban pathways of sustainable development mean at different scales, for varied sectors and in more specific operational and evaluative detail. Faced with such an overwhelming set of tasks there is a danger that ‘the urban’ will degenerate into a chaotic concept with no analytical or practical traction. This is a pivotal moment, not just for the realignment of global, national and local structures of urban governance, but also for the recalibration of the allied systems of urban research and donor support.

This paper begins by setting out (in Section 2) what is meant by an urban agenda, arguing that the normative innovation embodied in the post-2015 vision is a radical policy shift that will reverberate across science and practice over the next 15 years. At present, one Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) is explicitly about cities – ‘to make cites safe, inclusive, sustainable and resilient’ (henceforth SDG#11) – but the twenty-first century urban emphasis of multilateral policy will be given further impetus in the (still to be finalized) content of Habitat 3’s New Urban Agenda (henceforth NUA).[5] There is further evidence of an urban paradigm shift in sustainable development policy to be found in other expert-led agreements, such as the Sendai Framework on Disaster Risk Reduction or Paris Agreement on Climate Change.[6] In refining the post-2015 urban agenda beyond the schematic text of the formal agreements of the 193 member states and reconciling the different high-level commitments that speak to the urban issue, there is an unfortunate time pressure. Inadvertently, the schedule for the revision of the UN’s Habitat process, the core forum for debate on global human settlement and urbanization policy, was scheduled to follow immediately after the conclusion of the SDGs – leaving less than eighteen months to consolidate what is a largely new and untested global policy domain.

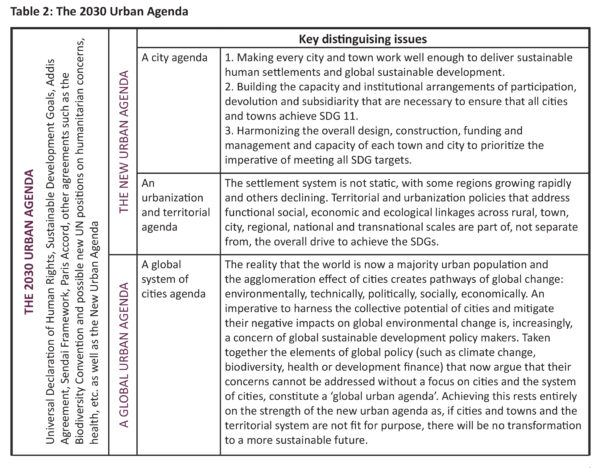

Given the sheer scale and complexity of already-agreed urban policies, the section concludes with a proposal to disaggregate the 2030 urban agenda in moving forward, incorporating but not conflating the thrust of Habitat 3 and other major UN position statements. The focus of Habitat 3 or the NUA is primarily to ensure decentralization, funding and institutional coherence to make individual cities and national territorial systems work more effectively in the fight for sustainable development – put crudely this is an expanded urban planning and governance agenda. This can be separated from the related concerns of the assessment of and response to the accumulated impact of all cities on global flows – of energy, migration, security, finance, biodiversity loss, etc. – which might be more appropriately styled as an Urban Global Change Agenda (UGCA) or science of cities.[7] The NUA and Global Urban Agenda (henceforth GUA) together are henceforth referred to in this text as the 2030 Urban Agenda, as there is no doubt that both the more focussed and managerial emphases and the broader attention to the environmental impact of cities can be found in the motivation and formulation of the urban SDG.[8]

Accepting that the city-centric thrust of contemporary policy has its origins in diverse communities of urban scholarship suggests that, while there is agreement that cities are important, there is not necessarily a shared philosophical or disciplinary understanding of what a city is or why it is relevant for sustainable development. Putting aside the very substantial ideological differences that emerge when policy choices have to be made, three frontiers of academic contestation are identified that will have direct bearing on how the research associated with the 2030 Urban Agenda is conceived and executed, namely (i) how the object of the city is defined, (ii) the nature of the science policy interface that is established, and (iii) the priorities given to urban research funding and capacity building.

2. The 2030 Urban Agenda: what is it and how is it different from earlier policy?

Orchestrating a city-centric understanding of sustainable development begins by understanding what the current cluster of policy announcements actually includes and why it is so distinctive relative to past policy positions. Clarity on the multiple references to cities in recent agreements lays the ground for identifying current priorities, gaps and future research needs. While it is understandable that the labyrinth of UN processes may irritate and even obfuscate, what needs to be highlighted at the start is the remarkable policy coherence that has emerged on the centrality of cities, all cities, in sustainable development. In generating these views not only were there multiple policy streams, but also the opportunity within each process for thousands of individuals and organizations, as well as all 193 member states of the UN, to draft and amend the final texts. Few cities, let alone nations, can claim to be as participatory. Out of these extensive deliberations, which typically draw directly from some aspect of science, it is possible to discern not just agreement on the need to foreground the urban question, but also potential divergence in the proposed direction that this apparently consensual focus might assume.

For purposes of clarity it is best to begin by breaking the recent urban policy commitments of UN system into three parts: The SDGs, Habitat 3 or the NUA and other recent and anticipated high level UN agreements that bind signatories to new urban commitments. While we are not suggesting that there is an inherent contradiction between these multiple overarching policy statements, it is clear that for urban transformation to occur a major task of alignment and co-ordination is required across scales and sectors. Within the UN system some tension in defining mandates for implementation of the 2030 urban agenda is to be anticipated. Already UN-Habitat, backed by the G77 and a strong African endorsement of the Nairobi-based agency, has signalled its intention of assuming a central role in implementing and co-ordinating global urban policy. The tricky thing is that, given lack of progress on Habitat 1 and 2 commitments and poor funding support,[9] UN-Habitat is not universally perceived as an agency that is capable of taking on a massively expanded global urban mandate. Capability aside, there is huge ambiguity over what exactly an urban mandate might entail and thus if any single UN agency should be made its global custodian. How the global mandate and its component parts are defined will thus be critical in establishing the institutional structures that are needed to support and refine the 2030 Urban Agenda.

From the perspective of science, the rationale for unravelling the multiple urban policy imperatives associated with the 2030 vision are much less concerned with internal UN institutional mandates than they are with the imperative of working out what drives change in cities and what could unlock a more sustainable urban development trajectory within a particular city and across the urban system. At this foundational moment of global commitment to urban transformation, it is essential to clarify the assumptions and expectations of improved urban governance, establishing the knowledge and practice gaps that will enhance or prevent the realization of the 2030 agenda, and being clear that the criteria by which global urban interventions will be judged are robust. Understanding what the 2030 Urban Agenda might mean for science thus begins with a robust understanding of what the policy proposals are and are not.

2.1 The SDGs and the Urban Question

The endorsement of the new stand-alone urban goal in SDG #11[10] to make cities safe, inclusive, resilient and sustainable is path-breaking, both within the UN system for the acknowledgement it brings of the developmental role of sub-national governments and paradigmatically for global urban policy, because it concedes that, in an urban world, cities and territorial policy are pathways to sustainable development.[11] However, SDG #11 is not the final sum of the urban commitments made at the UN Sustainable Development Summit in 2015.[12] Given that already more than half of the world’s population lives in cities, all SDGs will require urban execution, and across the SDG targets and indicators there are particular issues that have special urban salience. Proponents of an explicit urban agenda, many of whom were involved in the urban SDG campaign and are now involved in the preparation of the NUA, already speak of ‘SDG #11 Plus’. They note that the urban discussion of targets and indicators should cover all of the Goals[13] and that new financing arrangements will have to have to build in additional sub-national capacity if progress against the SDG targets is to be made.

It is not just the focus on cities that is new in the post-2015 global agenda. It is the way in which local territorial action is seen to be important to bigger global changes that is a radical departure from past thinking. The SDGs approved by the September 2015 General Assembly of the UN in New York changed the aspirations and practice of development in five substantive ways that apply as much to cities as to any other scale:[14]

- First, the SDGs are now universal. In other words, they set out one (minimum) standard for all nations (and cities) rather than focusing, as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) did, largely on conditions of poverty prevalent in the global south.

- Second, the SDGs are premised on the developmental interdependence of social, economic and environmental values, which gives much greater weight than ever before to the absolute ecological limits of human existence and the dangers of climate change. For cities, achieving this integrated mandate of sustainable development is very demanding, and suggests that there will need to be a fundamental transformation of most accepted practices of urban management.

- Third, the SDGs emphasize reducing inequality as well as poverty.

- Fourth, the SDG monitoring and reporting framework, enabled by innovations in geospatial science, complex statistical modelling and big data analysis, allows the integration of spatial and statistical analysis and the nesting of local, national and global indicators. This technological revolution in data allows greater flexibility in indicator selection and reporting, and so promises to refashion the measurement of global development. The spatial disaggregation of data, allowing for inter- and intra-urban analysis, along with the codification of informality, could be the opportunity for evidence-led policymaking to gain traction internationally.

- Fifth, the global development agenda is now being debated alongside issues of institutional capacity-building and global finance (SDG#17). Although the conclusions of the July 2015 Addis Abba meeting were disappointingly vague, the principle that funding for development and development priorities should be joined up, and made more viable at the local government scale, is also acknowledged.[15]

2.2 Habitat 3 and the New Urban Agenda

To take up the urban implications of the 2030 sustainable development agenda requires a profound reframing of global, national and local institutions. Initially the proposed innovation was to move away from the traditional Habitat 1 and 2 focus on housing and land[16] to concentrate on local action (devolution) across the whole settlement, not just some key sectors of special relevance to the poorest of the poor. Given the comments from regional stakeholders (especially those in Africa), it now looks certain that Habitat 3 will not only maintain a focus on housing and basic services, but will also include the national and even transnational urbanization process in an urban territorial planning mandate that is not just city focussed.[17] Clearly, this broader intergovernmental framing of the NUA, while possibly but not necessarily diluting the imperatives of addressing devolution and subsidiarity, underscores the urban and territorial role of national governments alongside that of local governments. National Urban Policies, a likely indicator of the SDGs, will be the instrument through which these multi-scale and multi-sectoral agendas will be mediated.

Beyond the issue of scale (city versus regional or national territorial policy), further discrepancies are evident in interpreting the ambition and scope of the NUA relative to the normative positions of the SDGs. The more conservative, but still demanding, view suggests that urbanization needs to be approached positively and that every place must be much better-run if sustainable development is to be achieved across the rapidly-expanding urban population. A second, more radical proposition is that improved urban governance is not enough. Instead a new approach to the fabric of cities and the organization and norms of urban life are needed – where every urban citizen’s lifestyle, every city service, every city, every city region and the system of cities are run in an entirely different way to guarantee that the collective urban condition secures, rather than precludes, global sustainability. For Habitat 3 and the NUA to take on both of these tasks, either of which is massively more progressive than what currently exists, is hugely ambitious. The deadline of October 2016 for final agreement on how this is all to be achieved would seem to make this ambitious dual reading of the post-2015 urban imperatives untenable, even while it may ultimately be desirable.

It is premature to offer a final assessment on what the NUA will actually be able to deliver. At present, the deliberations are not focused on the distinction between making cities and territories work better to achieve sustainability versus the radical transformation of settlements as the mechanism to meet global challenges such as the ending of poverty, the reduction of inequality, gender equity, deradicalization, dematerialization, ecosystem integrity, decarbonisation, etc. Rather, there is a loose assumption that the two approaches to the urban agenda are necessarily congruent. In practice, however, the bias in the NUA is to the former abstraction, i.e. collective local and national action to make all cities and territories work better in order to achieve inclusivity, safety, sustainability and resilience.

Using the zero draft and inputs from the Habitat 3 background papers and meetings, the expert policy groups and the regional and thematic meetings[18] as an indication of the policy thrust that is likely to emerge in Quito in October 2016, it seems that a profound rethinking of urban resource use in cities has not been embraced but that there are other major reforms proposed. The following substantive changes in international policy can be anticipated:

- A much stronger emphasis on the local state, including the critical issue of sub-national finance and civil service capability.

- Largely in response to Africa and other rapidly urbanizing regions, that the focus of the NUA will fall on urbanization and territorial policy as well as on the narrower institutional concerns of what makes cities and towns work (or not work) sustainably.

- The traditional emphasis on housing and human settlements has been expanded in favour of a more integrated settlement-wide understanding of the territorial relationship between planning, land, finance and infrastructure, but the focus on slum eradication will remain.

- Building on what the Global Urban Observatory[19] has already demonstrated, there is widespread concern about the availability and quality of downscaled data. While this is the case even in relatively affluent cities, the anxiety is particularly acute in cities where widespread informality, weak states and low levels of public resources mitigate against the rapid construction of robust and credible monitoring systems.

- Despite major lobbying by civil society and the Latin Americans, it is unlikely that the right to the city will be endorsed. Not only is there overt opposition to this from the United States, but the concept itself is also not universally understood. What is likely to emerge from the rights deliberations is a much clearer focus on urban land rights and tenure security.

- New mechanisms within and beyond the UN, possibly those advocated by the General Assemble of Partners,[20] are likely to be established into the implementation and monitoring phase of Habitat 3. It is unclear at this stage if UN-Habitat will lead or be a strategic player in a wider global urban policy consortium going forwards.

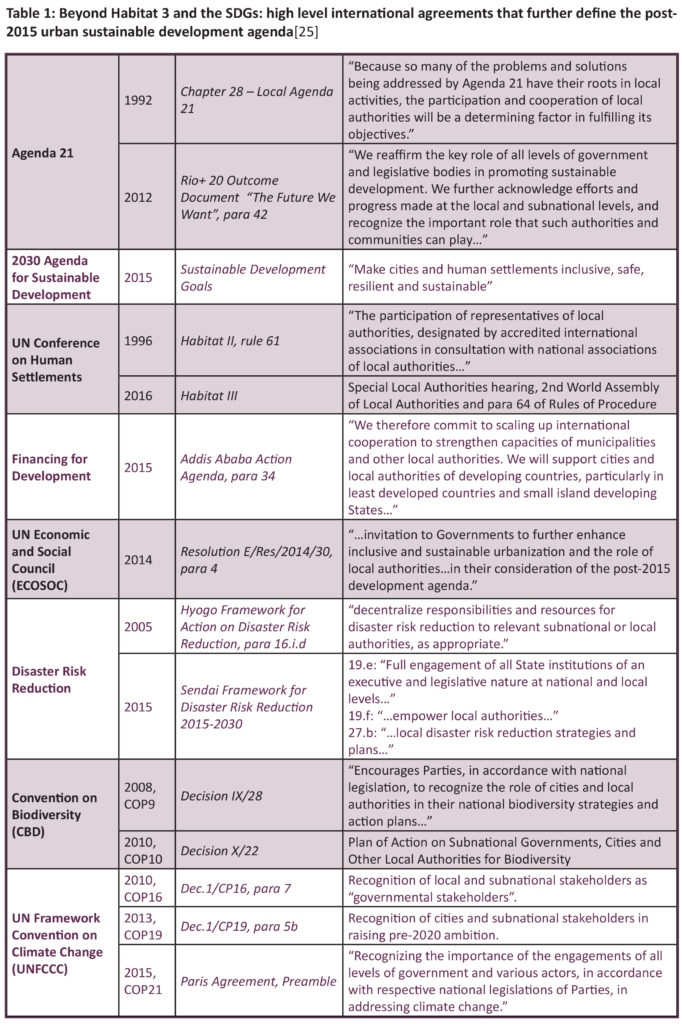

2.3 The Urban Question in other recent UN Agreements

The SDGs and Habitat 3 are not the only part of the UN where cities are discussed or where high-level agreements have clear implications for the overall urban and territorial agenda, as well as for the increasingly important role of local government. A series of international milestones have offered ‘urban’ input to the discussion on sustainable development and global governance (Table 2), beginning with the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030[21] adopted by UN Member States in March 2015. This was followed in the same year with the Addis Ababa Action Agenda (AAAA)[22] on financing sustainable development in July that stressed fiscal decentralization and municipal finance. Other sector deliberations on how to deal with cities, such as those in the World Health Organization (WHO), UN Environment Programme (UNEP) and UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), are also underway.[23] The increasingly city-centric focus of global policy culminated with the SDGs in September 2015 that included a new dedicated ‘urban’ goal. Shortly afterwards, in December, the UN Framework Convention of Climate Change (COP21) Paris Agreement, COP21, affirmed the 2030 universal commitment to cities. Other sectors, such as health, humanitarian response and human rights, are also preparing major new global policy positions on the urban question.[24] The issue is not whether Habitat 3 should align with these other agreements; there is consensus between all parties of the value of policy coherence. The more difficult tasks are to delineate manageable portfolios of action, prioritization, sequencing, assessment criteria and monitoring and review processes for the post-2015 Urban Agenda.

2.4 Post-2015 Urbanism: Global urban policy and/or a new urban agenda?

In thinking about the urban uptake of the post-2015 ideals, it may be useful to distinguish between the broad mandate of a 2030 Urban Agenda that includes a GUA made up of the diverse policy positions that touch urban issues together with the sharper NUA that will be approved by the UN member states at Habitat 3 in Quito Ecuador in October 2016. The former (the GUA) refers to the suite of international polices that reflect the new inclusion of cities as a fundamental pathway of transformative change in macro processes. These are policy terrains such as biodiversity, climate change or health that were, hitherto, largely unconcerned with space, scale, location, or sub-national government and where cities have only recently been identified as significant factors of policy concern.[26] The latter (the NUA) is the refined and much-expanded Habitat position that, as of October 2016, will argue that the sustainable development focus of human settlement and urbanization needs to be widened and the involvement of local government embraced. The post-Quito Habitat focus is on making cities work better through an emphasis, not just on key sectors like housing, but through an institutional understanding of devolution, subsidiarity and the management of cities (especially land and finance). As indicated earlier, the two strands of intellectual thought about how much has to change in urban management are related. Ambitions for achieving the 2030 Urban Agenda will come to naught if there is not both a dramatic improvement in how cities everywhere are run and, additionally, a fundamental normative shift in the understanding of how cities and urban lifestyles drives global change. By the logic of global urbanism, cities are important not simply because these are the places where an increasingly large proportion of all people reside and where the SDGs must be realized, but also because cities and urban life change global dynamics. How cities are managed therefore matters for sustainability, and the NUA must provide the means to positively shift urban development trajectories. Indeed, because what happens in individual cities is a causal mechanism of larger changes, it matters how effectively each and every city is run: there is a universal imperative to improve urban management.

The collective or aggregate interest in cities is one factor that sets the GUA apart from the NUA. The other is that whereas urbanization and human settlements are the sum interest of the NUA, with key battles centred on getting adequate local power and money, the GUA parties have to battle issues unconnected to urban spatial and territorial dynamics, such as consumption, population, technological change, resource regulation etc. (Table 2). Distinguishing the NUA and GUA may be useful operationally for breaking down an overburdened global policy machine, and need not suggest fragmentation or policy incoherence. The notion that there are distinct and potentially competing views of complex problems is an idea that is increasingly accepted by the scientific community that is engaged with the urban system.[27] Sector specialists, while willing to acknowledge the complexity of their own fields of operation, are typically less accommodating of urban dynamics that operate beyond their established domains of expertise. Indeed, a major contribution from the scholarly community to the 2030 sustainable urban agenda will be to guide the global community in thinking through the inter-sectoral complexity of socio-technical interactions entailed in making radical changes to earth’s urban systems.

The collective or aggregate interest in cities is one factor that sets the GUA apart from the NUA. The other is that whereas urbanization and human settlements are the sum interest of the NUA, with key battles centred on getting adequate local power and money, the GUA parties have to battle issues unconnected to urban spatial and territorial dynamics, such as consumption, population, technological change, resource regulation etc. (Table 2). Distinguishing the NUA and GUA may be useful operationally for breaking down an overburdened global policy machine, and need not suggest fragmentation or policy incoherence. The notion that there are distinct and potentially competing views of complex problems is an idea that is increasingly accepted by the scientific community that is engaged with the urban system.[27] Sector specialists, while willing to acknowledge the complexity of their own fields of operation, are typically less accommodating of urban dynamics that operate beyond their established domains of expertise. Indeed, a major contribution from the scholarly community to the 2030 sustainable urban agenda will be to guide the global community in thinking through the inter-sectoral complexity of socio-technical interactions entailed in making radical changes to earth’s urban systems.

3. Scholarship and the 2030 Urban Agenda

In galvanizing the academic project as part of a wider effort to pursue sustainable development objectives, it helps if everyone has the same problem in mind or understands where their points of departure are different. Unfortunately, this is rarely the case with urban studies, where efforts at interdisciplinary collaboration and co-production are not always as clearly set out as they could be and at best result in confusion, at worst in muddled thinking that obfuscates rather than clarifies causation. Mindful that the precise parameters of urban sustainable development are still poorly formulated, this section looks at how the 2030 policy agenda and its intellectual and research informants might evolve beyond Paris, Sendai and Habitat 3. Overwhelming expectations, the complexity of the problems to be addressed, the range of urban stakeholders that must be incorporated and numerous other ambiguities will emerge as attention shifts from the 2015/16 pre-occupation with pushing for an urban agenda, to implementing and reviewing it. It is unlikely, no matter how successful Habitat 3 deliberations are or how skilled the negotiators prove to be, that an uncontested and well-defined plan of urban action will emerge. To this end there will be a much-expanded demand for urban research that speaks to the need to consolidate and extend the evidence base of the global policy agenda, as well as calls for some mechanism for revising, monitoring and reviewing policy. It may well be that the research community also plays an important part in helping to co-ordinate, integrate and prioritize across the complex parts of the multi-faceted urban question.

The urban is a messy terrain, both intellectually and practically. It draws together very diverse constituencies such as mobility, public security, housing, sanitation, city planning, city preservation, to name a few, and quickly becomes everything to everyone. Alternatively, studies of the city, the city system and the city in global change are fields that are so contested that scholars can consume all their efforts navigating an internal academic world that bears little relationship to operational concerns and that has little or no relevance for anyone outside of a self-defined cohort of specialists often guided by their professional codes. If current practices of academic isolation persist and urban studies (and its fragmented constituent parts) fail to effectively engage each other or adequately distil the dynamics of and priorities for a transformative urban agenda beyond their narrow areas of interest, researchers will distort, delay and undermine the positive implementation of the 2030 Urban Agenda. Three positive domains of action for the academy are thus: (i) clarifying the objects of urban analysis, (ii) putting in place appropriate mechanisms that strengthen the science policy interface, and (iii) having clear defensible priorities for research funding and capacity building.

3.1 Measurement, definitions and data: Finding a common urban object for evidence-based engagement with the 2030 Urban Agenda

Recognizing that ‘sustainable urban development and management are crucial to the quality of life of our people’, the UN General Assembly introduced SDG# 11 that is dedicated to the development of cities. This and all other goals require sub-national as well as national sustainable development indicators that are tailored for measuring progress towards the achievements of the urban agenda. The problem, however, is that we do not have a globally accepted definition of an urban area.[28] Clearly, if nation states are to measure their progress towards the achievement of the urban SDGs, they need to have a standard definition of an urban settlement so that their measurements are comparable over time and with other countries. Although it is already acknowledged that the absence of adequate and ‘local’ statistics will be an obstacle to the measurement of indicators for urban settlements,[29] this is only part of the problem. Even if we had adequate and credible statistics for urban settlements,[30] we would still have to agree on a universal definition of an urban settlement to make these indicators comparable and to enable the scaling up or aggregation of progress on urban transformation. This paucity of robust data is as much and more a problem for science as it is for practitioners wanting to make useful assessments of urban spaces or compare locations.

This lack of a universal definition of an urban area is not a problem restricted to debates about developing indicators for the SDGs. It is also a problem that has bedevilled research on comparative urbanization and it is now becoming a central debate in the sub-discipline of ‘urban studies’. In the case of comparative studies of urbanization, countries use widely different definitions of urban settlements with the result that estimates of the rate of urbanization in different countries are not comparable.[31] For example, one definition is based on the criteria of population size and density. Some definitions of urban settlements require most of the employed population to be engaged in non-agricultural economic activity. Others use the administrative boundaries of local-level state institutions such as municipalities, town committees or cantonment boards. Yet others define urban settlements on the provision of facilities and infrastructure such as schools, street lighting, paved streets, medical centres, piped water and sewerage.[32] For scholars from the natural sciences, the question, ‘What is urban?’ is extremely broad, extending not only to processes within city boundaries, but far beyond in analyses of the multiple dimensions of urbanization and how they interact with other global drivers influencing land use, biodiversity loss, resource extraction, carbon emissions, global and regional climate change, economic activities, human wellbeing, emerging vulnerabilities to pandemics over large geographical areas, etc.[33]

Given the recent changes, policy makers (along with research and funders) will be keen to decide on a universal understanding of what makes an urban settlement. The definition of the urban, a critical starting point of a post-2015 response, however hinges on philosophical issues, reinforcing the argument that the scholarship that is needed for a 2030 Urban Agenda is not only to be found in applied research.

When we think about urban settlements, it is tempting to assume that our concepts of cities and human settlements bear a direct correspondence to the real social world. If this were true, then it would be logically possible for us to agree upon a single definition of an urban settlement that corresponded perfectly with all the complex details of urban settlements as they exist in the real world. However, modern philosophy of science, in the form of ‘critical realism’, now rejects this crude empiricist philosophy. Instead, scholars now propose that knowledge should be understood as something that is separate from the reality that it tries to represent and understand. In this view, our perception of the social world is therefore always mediated by our conceptions of it. This is not to say that our knowledge of the social world is determined by our concepts. To the contrary, evidence-based scientific knowledge is created through the critical engagement between our conceptual descriptions, on the one hand, and our conceptually mediated observations, on the other.[34]

If we accept this line of reasoning, then it would be true to say that our concept of an urban settlement is a ‘thought object’, which exists in the realm of knowledge. By contrast, the urban settlement that we are observing exists as a ‘real object’ in the realm of the real world.[35] This is an important distinction because real objects are what the philosophers call ‘concrete’ objects that exist as complex, multifaceted phenomena. By contrast, thought objects are much simpler than real objects, taking the form of what we call ‘abstractions’, which are only partial, or one-sided, descriptions of real objects. This is not to say that abstractions are feeble imitations of concrete phenomena. On the contrary, precisely because abstractions isolate their significant features, they are useful for providing an understanding of concrete phenomena. An everyday example can be provided by how we navigate our way through an unfamiliar city using Google Maps. If we view the map using ‘satellite view’, the aerial photographic image is much more complex and difficult to understand than if we use the ‘map view’, which shows only streets, street names and block outlines. The ‘satellite view’, with street labels turned off, is more difficult to use for navigation because it much more closely approximates the concrete and complex phenomenon of the city, with its houses, trees, factories, parks and bridges. By contrast, the ‘map view’ is a typical abstraction, which represents only those features of the concrete city that are helpful for navigation: the streets and street names.

An important feature of abstractions is that they can be substantially different, even when they are used to study the same concrete phenomenon. In other words, an abstraction can select different partial features of the concrete phenomenon without doing any violence to empirical observations of the phenomena. Precisely what features we choose to include in our abstractions and what we exclude from them, is a choice that we make. To use the analogy of Google Maps again, we can use the ‘menu’ to select different kinds of abstractions, from public rail ‘Transit’ to ‘Bicycling’. The result is that we can view a street map with an overlay of the passenger railway lines and stations, or we can view it with an overlay of the streets recommended for cycling. These overlays are completely different abstractions from the same concrete city.

Many theoretical debates in social science are disagreements about what abstractions we should make rather than disagreements about the interpretation of particular objects. The debate currently raging about the nature of ‘the urban’, in which scholars discuss multiple abstractions, only to talk past each other rather than engaging in productive debate (Table 3), is apposite.

Table 3: Selected urban abstractions in the contemporary academic literature

| Urban abstractions | Key idea (often accompanied by a direct critique of the core propositions rather than the interpretation of the particular research objects) |

|---|---|

| 1. Planetary urbanism | The urban age is much more than demographic. Everything, everywhere is so integrally part of the urban process that no clear conceptual or intellectual boundary can be meaningfully used to delineate the urban and the non-urban condition.[36] |

| 2. Urban anthropocene | A distinct post-Holocene epoch, where evidence of human activity, associated with agriculture, urbanization and carbon based lifestyles is found in the geological structures.[37] |

| 3. Urban ecosystem services | The view that cities depend on and benefit from the integrity and value of natural resources such as water, air or soil for their vitality as much as or more than they do from human skill or financial resources.[38] |

| 4. Ordinary cities | There can be no conceptual hierarchy in generalizing about urban processes. Because every city is different, local context and the experiences of less well-understood places must be foregrounded to counter misleading generalizations based on well-researched places.[39] |

| 5. Southern urbanism | Dominant Western theorization about the urban process is hegemonic and distorted because it ignores local ideas and philosophies and so the distinctive urban experiences of marginalized southern cities are not valued and may be inaccurately represented.[40] |

| 6. Regionally distinctive urbanisms – e.g. Africa | Demographic dominance means that the twenty-first century is one of Asian urbanism.[41] The divergence between the local or regional urban realities in Africa requires explanation of urban processes beyond that suggested by the existing Northern literature. Specifically, rapid population growth, poverty, exposure to risk alongside weak states and often absent local government means that new forms of urbanization are not well documented or properly understood.[42] |

| 7. The informal city | Pervasive informality and insecurity plus the absence of any formal employment or state capacity makes urban life precarious, fluid and contested. The only way to understand the city is to track everyday negotiations.[43] |

| 8. Cities as accumulation | Cities everywhere are defined by economic agglomeration, creating a clear definition and focus for any urban intervention.[44] |

| 9. Global cities | Certain cities, London, Paris and Tokyo in particular, assume a particular pinnacle status in the world economy because of the concentration of financial and service sector activities. They also present a particular class structure because of this.[45] |

| 10. Resilient cities | Cities develop capacities to help absorb future shocks and stresses in the social, economic, and technical systems and infrastructures, so as to still be able to maintain essentially the same functions, structures, systems, and identity over time.[46] |

These scholarly disagreements over which abstractions are appropriate for the study of urban settlements contain a lesson on how we should think about conceptualizing the 2030 Urban Agenda (and also the GUA and the NUA), just as it does about defining urban settlements for the purpose of measuring sustainable development indicators. This lesson is simply that there is no single definition of ‘the urban’ that can be used as a basis for measuring different sustainable development indicators and there may be no single institutional home for the urban agenda: either globally, nationally or locally, or in one discipline rather than another. Instead, we should be prepared to accept that our definitions of urban settlements will be different, depending upon our abstractions and hence the indicators that we are measuring. Finding a global nomenclature or classification for the urban in the post-2015 Agenda must surely be one of the first tasks of implementation post-Quito. In setting out this ‘urban base-line’, it will be important to draw on the views of scholars and experienced leaders who are able to navigate, even arbitrate, what is most useful or important from within and across the scholarly literature, what is implied by existing data systems and what would be essential to build into future urban metrics. To do this they must be both intellectually credible and connected enough to practice that they can affirm, amend or insert new knowledge with the power to change sustainable urban development practice.

3.2 Co-production and the science policy interface

What should be clear by now is that there have been rapid changes in the global urban policy environment, with Habitat 3 providing a further collective opportunity to refine the place of cities and urbanization in the sustainable development agenda. There is however a question for the research community over how, post-Quito and in the light of other major city-centric global agreements, the 2030 Urban Agenda might be further advanced in an institutional way that maintains an active dialogue between scientists and policy makers within and across what have been described here as the NUA and GUA.[47]

The UN, the current host of the urban sustainable development processes, has over the decades evolved an elaborate but clumsy participatory process where science is able to have a voice alongside other civil society stakeholders.[48] The representation of scientists in the UN takes place primarily through the civil society participatory structure of Major Groups that was established in Rio in 1982, whereby an institution from the sector acts as a contact or organizing point for the constituency, allowing representations to be made to the member groups who will finally vote on policy. In the case of Sendai, the SDGs and Habitat 3, the International Council on Science (ICSU) served as a contact point for the Science and Technology Major Group, though this is not a fixed ‘appointment’. In addition to the direct representation of the scientific body, individual scholars are active in each of the stakeholder groups and the work of scholarship infuses many of the arguments made for change. Organized research-funding also plays a critical role in determining what issues are prescient in the knowledge realm – philosophically, methodologically and geographically – but this indirect influence should not be conflated with having a tangible presence in positioning research in policy making, implementation and review.

In the case of Habitat 3, a somewhat different process of organized participation has evolved that draws from but expands the logic seen hitherto seen in UN global deliberations. Under the capacious leadership of Prof. Eugenie Birch, a special initiative of the UN-Habitat sponsored World Urban Campaign known as ‘the General Assembly of Partners’ (GAP), was set up to support stakeholders’ engagement and contributions in the lead up to the Quito conference – for example, by making it possible for civil society to attend regional and thematic meetings, and running the web platforms on which complex information flows associated with a global process depend. GAP consists of 15 Partner Constituent Groups (PCG) that reflect but also extend the traditional range of stakeholders identified by the Major Group system. The GAP PCGs currently include: local and sub-national authorities; research and academia; civil society organizations; grassroots organizations; women; parliamentarians; children and youth; business and industries; foundations and philanthropies; professionals; trade unions and workers; farmers; indigenous people; media; and, the most recent addition, older persons. Volunteers run GAP and its membership is open to individuals and organizations. The PCGs chair and co-chair effectively act as contact points to wider networks, and the GAP webpage provides general information on Habitat 3 to all.[49]

While GAP’s overall leadership and its dependence on one UN agency (UN-Habitat) are contentious for some, the group has been diverse, effective and active. To some extent GAP has consolidated the even more informal group of civil society activists in the SDG process, which included a very significant (even dominant) academic voice, who mobilized for the urban SDG.[50] One suggestion to date is that the GAP be continued to ensure on-going civil society inclusion in post October 2016 engagement with the NUA, so as not to have to wait until the Major Group process for Habitat 4 is initiated by the UN in 2036.[51] As yet, however, the existence of GAP as an ad hoc platform for civil society leading up to Habitat 3 in no way institutionalizes any longer term dialogue – either around the NUA or the GUA, though it is possible that a monitoring mechanism for the NUA may still be written into the zero draft that will be the outcome of the Habitat 3 open meeting in New York in April 2016.

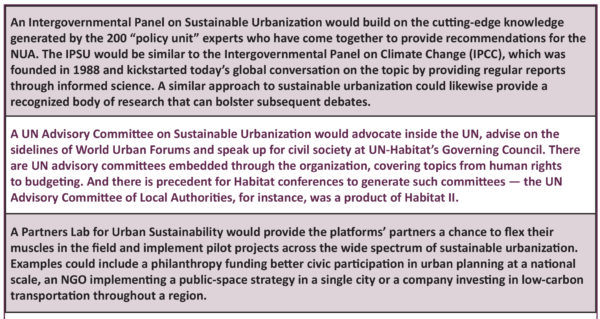

In practice, the post-2015 consensus that cities are critical pathways of change is way ahead of any clear or shared vision for how best to achieve the necessary transformations required of existing cities – or those that are yet to be built. Increasingly loud voices (not just those within GAP) have thus argued that, analogous to the experience of climate change, there may be a need for an Intergovernmental Panel for Sustainable Urban Development – an ‘IP for Cities’, albeit in the form of a structure that has local rather than national government leadership. GAP’s proposal for an Intergovernmental Panel on Sustainable Urbanization (IPSU) (Table 4), by which they mean a knowledge platform that builds on the legacy of the Issue Papers and Policy Unit process of Habitat 3 that were assembled to reflect diversity of many kinds and to draw from expertise beyond member states has clearly influenced the Zero Draft which (paragraph 171) suggests:

We also stress the need for UN-Habitat and other relevant stakeholders to generate evidence-based and practical guidance for the implementation of the New Urban Agenda and the urban dimension of the Sustainable Development Goals, in close collaboration with Member States and through the mobilization of experts, including the General Assembly of Partners for Habitat III, and building on the legacy of the Habitat III Issue Papers and Policy Units preparatory process, to consolidate links with existing knowledge and urban solution platforms relevant to the New Urban Agenda. In this regard, the creation of an International Multi-stakeholder Panel on Sustainable Urbanization, coordinated by UN-Habitat in collaboration with the rest of the UN System, might be considered.

The purpose of the IPSU mechanism that GAP has proposed is to consolidate links to existing knowledge platforms of relevance to what emerges from Quito. The envisaged scope of the IPSU, at least in the draft document, confirms not only the centrality of UN-Habitat but also concern with city and territorial concerns of the NUA, rather than some of the larger issues, that might be taken up from the GUA: “It will also evaluate and generate policy relevant, but not policy prescriptive, research around topics critical to sustainable urban development, for instance, the form and configuration of cities and regions, livability, human rights, labour rights, equity, and governance.”[52]

Significantly, the GAP proposals are not limited to the IPSU, though their suggestion of a UN Advisory Committee on Sustainable Urbanization, while alluding to the broader remit of the 2030 Urban Agenda, is conceived of as an internal UN structure, thus bypassing most of the key urban stakeholders and possibly negating the impetus to decentralization envisaged in Goal # 11. Recommendations for a Partner Lab and a Partner dashboard do speak to the awareness of local ownership of the NUA, at least at the level of implementation.

Table 4: GAP proposals Post-Habitat 3 implementation structures[53]

If the ambitious plans GAP has tabled were to be achieved in full, the institutional questions about its genesis and on-going location in UN-Habitat would become critical. Moreover, in picking up the substance of the wider 2030 Urban Agenda and the interface of the NUA and GUA, the mandate of any future institutional mechanisms for including non-UN members in the global deliberations on sustainable urban development would need consensus and support, especially from local government. By virtue of the traditional UN focus on the nation state, local government associations such as the United Councils of Local Government or the Commonwealth Local Government Association, as well as bodies like Cities Alliance or the International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives (ICLEI), tend to give a country level bias to the urban agenda. Even if a UN member structure were to take the lead, there is an acknowledged concern about where any global urban governance hub might reside within the multi-lateral structures, as UN-Habitat is not the strongest of the UN agencies. Moreover, its traditional remit of human settlements, even in an expanded form that encompasses urbanization, fails to cover all the core pillars of the NUA and the Nairobi-based agency was never intended to provide support for the much wider urban implications of the GUA that have emerged. For the research community this politics is important – not least in defining the points of contact and mandate of the science policy interface.

If the ambitious plans GAP has tabled were to be achieved in full, the institutional questions about its genesis and on-going location in UN-Habitat would become critical. Moreover, in picking up the substance of the wider 2030 Urban Agenda and the interface of the NUA and GUA, the mandate of any future institutional mechanisms for including non-UN members in the global deliberations on sustainable urban development would need consensus and support, especially from local government. By virtue of the traditional UN focus on the nation state, local government associations such as the United Councils of Local Government or the Commonwealth Local Government Association, as well as bodies like Cities Alliance or the International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives (ICLEI), tend to give a country level bias to the urban agenda. Even if a UN member structure were to take the lead, there is an acknowledged concern about where any global urban governance hub might reside within the multi-lateral structures, as UN-Habitat is not the strongest of the UN agencies. Moreover, its traditional remit of human settlements, even in an expanded form that encompasses urbanization, fails to cover all the core pillars of the NUA and the Nairobi-based agency was never intended to provide support for the much wider urban implications of the GUA that have emerged. For the research community this politics is important – not least in defining the points of contact and mandate of the science policy interface.

The future of how civil society in general and the research community in particular engages the on-going urban policy question across the NUA and GUA is thus tied up not just with the implementation of Habitat 3, but in far larger institutional implications of the post-2015 Sustainable Development Agenda monitoring and review process. Securing any amendment to global urban policy consensus implies a close assimilation of city, national and international actors, something almost impossible within the current structures of the nation-state dominated UN. There are moreover major internal institutional hurdles for finding a home for urban development within the UN, beyond the much narrower human settlements mandate held by UN-Habitat.

Leaving aside the appropriateness of the UN itself, it is far from evident who in the global system might best support or lead the global urban agenda. Academics, like local government, are likely to question the essentially flat participatory structure of existing UN participatory models used to build a common urban vision. Collective processes, such as that produced by the Major Groups, weight the contributions of all participants equally and are not able to draw from expert or specialist knowledge, nor do they have the means to test the veracity or importance of claims about the viability of the large scale urban changes proposed or their impact on the overall global system. GAPs proposal for differentiation in the post-Habitat 3 governance mechanisms, while it could be further refined, reveals great insight in this regard and it is beholden on the science community to engage in the lead up to Quito to ensure that the institutional modalities that will be most effective for securing an on-going opportunity to use evidence to inform the urban policy gains made.

This is a crucial moment for the whole science policy community to position the urban agenda strategically and account for progress in sustainable development in a credible fashion. How the GUA in general and the NUA in particular are taken up will reverberate across professional practice, through the transnational networking of cities and the activities of urban civil society movements. Taken in the broader sense of the GUA, or even in the more tightly defined framing of the NUA, the sheer range of issues wrapped up in the urban policy domain begs for clarity and co-ordination in the implementation, monitoring and refinement of policy positions. Getting greater conceptual clarity on the distinction between when and how cities are drivers of global change, on the one hand, and understanding how cities can be made to work for rather than against sustainable development on the other, is a scientific priority.

Efforts towards defining the content, outcomes and metrics of a global urban agenda, and its interconnection with tracking and assessment demands for SDGs, AAAA and COP21 (the GUA), have spawned multilateral discussions within and beyond UN-Habitat. How will we know the urban progress in sustainable development, and how will the activities of cities, more and more at the heart of global affairs, be tracked? Who, to paraphrase the IPCC mandate, will be tasked with offering the scientific, technical and socio-economic information relevant to understanding the knowledge base of sustainable urban development, its potential impacts and options for the broader 2030 urban agenda?

It is not just the scope of the 2030 Urban Agenda that is overwhelming; there is also the problem of creating a monitoring system while policy direction is still under construction. Defining an entirely new mode and scale of development practice, as is implied by both the NUA and GUA, creates challenges not least in selecting (from scratch) the right sub-national targets and indicators. The essential problem is that ‘urban’ indicators are scientifically and operationally untested in the way that they are in more established areas like poverty, water, health or education.[54] If, for instance, we have to attest the (goal 11.3) “enhancement” of inclusive and sustainable forms of participatory planning, then measures and reporting mechanisms need to determine what ‘counts’ as participatory, which types of planning processes are to be assessed, and what local, regional and national threshold of community input in planning are to be maintained. Even in less ambiguous areas, new sub-national metrics will require more scientifically robust monitoring, calling for geospatial data, flow analyses and longitudinal assessments.[55] In many African and Asian cities this level of information is almost impossible to envisage. The debate on monitoring then presents a key science-policy juncture of our time: it raises questions as to how to track and define the progress, as much as it questions how to set, scientifically, the priorities for urban policies in developing and developed cities alike.[56] One purpose of a global research and advocacy leadership structure for cities would be to review the integrity of the already identified metrics of the various UN agreements (including the SDGs) against the objectives of the GUA, the NUA and the 2030 Urban Agenda as a whole, gradually refining and enhancing the overall post-2015 sustainable development monitoring process across cities, nations and in the wider global systems.

Central to how the urban agenda unfolds are the metrics that are selected to track progress and the credibility of the organizations that hold and produce the outputs. A number of organizations and initiatives have already begun casting control and asserting capacity over the science-policy juncture of post-2015 data systems. On the one hand, the UN Foundation is at least provisionally tasked with some degree of control over SDG progress monitoring, but large actors in sustainable urban development like the World Bank have also been vocal. In March 2015, at its forty-sixth session, the UN Statistical Commission created an Inter-agency and Expert Group on SDG Indicators (IAEG-SDGs), composed of Member States and including regional and international agencies as observers. UN-Habitat itself relied heavily on civil society and the scholarly community to develop the basis for the NUA as a suite of ‘policy units’ and ‘issue papers’ involving a wide spectrum of experts. Despite the widely recognized importance of indicators, however, none of the issue papers or policy units was directly tasked with the problem of policy evaluation, though there are numerous references to the centrality of data across the preparatory work for Quito. The formally designated goals, targets and indicators are only one aspect of a wider policy-monitoring machine. To ensure its relevance, the international community must not only align the monitoring systems of the different parts of the urban policy machine (within UN-Habitat, the urban bits of the WHO, UNHCR, ILO etc.), but must evolve over time in response to bottom up concerns as issues change and data improves.

From the perspective of the research community, a view unanimously shared by other key stakeholders such as those participating in GAP, the urban agenda cannot be left to nation states or individual UN agencies. In tandem with the formal preparations for the 2016 Habitat 3 meeting under the auspices of the GAP,[57] there are other bottom-up, networked, semi-private and academic initiatives debating the role of cities in global change, building on an international tradition of policy sharing and critique. For instance major global city networks produce regular assessments of urban action progress. The regular GOLD report of United Cities and Local Government (UCLG) on democracy and governance, and C40’s flagship CAM review of climate action reveal the significant capacity that is directed at tracking urban change and understanding the collective challenges faced within cities or generated from cities. Likewise, hybrid initiatives, like the Cities Alliance Joint Working Program to support Habitat III delivery and implementation (gathering countries, private sectors and research bodies), have an important input in the process of setting and nuancing the global urban agenda. Other active actors in the sector include the Commonwealth Local Government Council, the World Council on City Data and the International Council for Science (ICSU), who have played a scientific convening role in the SDGs, Sendai and Habitat 3.

There is thus no shortage of urban expertise, including at the global scale, but as yet there is little consensus on how (beyond entrusting UN-Habitat with the 2030 Urban Agenda) concerned and knowledgeable parties might gather together to work in the period until Habitat convenes again until 2036. Worryingly, the immediate priorities of global urban development and the institutional and substantive mechanisms for urban assessment that will drive funders and donor programmes in the shorter-term are poorly defined. Habitat 3 is likely to provide the initiative on how to shift city management in line with the post-2015 vision, with a clear emphasis on subsidiarity, data, finance and land. These are necessary and fundamental reforms, but they may not be sufficient for realizing all other elements of the 2030 Urban Agenda.

What is clear is that the last five years represent a fundamental shift in global thinking about how important cities are and why they can make a profound difference to our common future. Critical recognition, requiring action to ensure subsidiarity and devolution, has been made about the role and responsibility of cities in sustainable transformation. But the urban journey has just begun. Given the scale and importance of the question for delivering social, economic and environmental sustainability, more time and capacity is needed to integrate potentially competing imperatives, to design the detail of the governance arrangements of a global urban mandate that feeds off the NUA, to establish a set of appropriate universal indicators and to create a leadership cohort that will hold the ambitions of the global agenda for cities. There are many potential mechanisms for this and the GAP suggestions point to the imperative of using multiple mechanisms in building a global urban governance machine.

For scientists concerned with evidence-based policy making, something like the IPSU, an Intergovernmental-like Panel or a committee of urban elders, that holds not just the NUA but also the GUA as its mandate, seems especially appropriate. As the IPCC[58] and IPBES[59] experiences demonstrate, systematic monitoring can strengthen the effectiveness of multilateral agreements, and even usher in substantive policy change, such as seen in the MDGs-SDGs transition, which gave substantively more weight to environmental concerns. The establishment of a mechanism recognized by both the scientific and policy communities to synthesize, review, assess and critically evaluate relevant information and knowledge on cities will however hold no legitimacy if the ‘Panel’ is convened by national government and excludes local government and civil society. This is not the only barrier: the current IPCC structure has itself been questioned, and it is undergoing some degree of reform prompted by calls for more flexible reporting and a questioning of the complexity of a single synthesis report. A further problem might be that deliberation on the Global Sustainable Development Report suggested that it was unlikely that a UN-sanctioned mechanism would be established on sustainable urban development within the SDGs framework.

Whatever its format, the logic of a global urban governance mechanism acknowledges that there are some transnational drivers of urban change, and also embraces the idea that the collective or amalgamated impact of how all cities are run will determine our common future. The post-2015 logic of ‘leave no one behind’ thus becomes ‘leave no city behind’. This is new research, donor assistance and governance terrain, and the flurry of pro-urban agreements of the last two years will not be sufficient to settle priority urban development interventions. City-level engagement in international deliberations presents a different granularity from that required by inter-national processes, thus raising critical scientific issues (as with data consistency across vastly different realities) and political issues of central-local governmental relationships that overlap with already sprawling demands for devolution. The clearly well meaning but extraordinarily ambitious calls to acknowledge ‘the urban’ as a driver or pathway of change assumes that various kinds of natural and social scientists can be brought together to engage on the big patterns of urban transition and to speak, if not with one voice, at least with some coherence, to policy makers who have to juggle competing priorities. This kind of complex science-policy interaction requires a wise distillation of priorities, appropriate institutional mechanisms and – perhaps most critically – the fostering of global research leadership for global urban governance.

3.3 Post-2015 research focus and enabling mechanisms

Given the complexity of the urban issues outlined above, the imperative to increase the absolute volume of research on cities, territories and the city in the global system should be abundantly clear. Part of this is overcoming past rural bias and part is the need to dramatically expand the overall research coverage given the pace of urbanization and urban growth.[60] There are the additional imperatives of critical assessment and review – with respect to both the expanded city and territorial commitments of the NUA and contribution of cities to bigger forces of global environmental change. Beyond facilitating expanded research output from individuals and research consortia, there is an opportunity to establish an inclusive yet coherent cohort of scholars who are able to engage meaningfully and knowledgeably with policy makers and practitioners at the global, not just national and local scales. To this end it is important to assess, and possibly reconfigure, national and international research funding architectures, which are currently not very well placed to respond to the diffuse multi-scalar and multi-disciplinary concerns of urbanists at this critical moment of policy realignment. In this regard there are three immediate areas of critical concern, beyond large-scale extension of the funds allocated to urban research of all kinds:

(i) Interdisciplinarity and/ or better defined urban abstractions?

There has been a proliferation of disciplines that have taken up an elevated urban research focus, especially in affluent societies. This resurgence, using a range of research methods and theories, played an important role in enabling the global endorsement of cities as a new and important focus of the universally applicable 2030 agenda.[61] The emergence of a form of urban optimism in European and North American social and natural science in the early 21st century was significant in legitimating the claims made for the importance of cities in the SDGs and the post-2015 agenda. What is most significant about the so-called ‘new conventional wisdom’ about cities in the social sciences is that it emphasizes urban processes as sites of opportunity and potential, and not just as problems, thus providing many points of policy connection between knowledge and practice based innovation.[62] Natural scientists working on cities have been similarly concerned to demonstrate that cities need not be environmental sinks.[63]

The scholarly assumption that there are a series of positive feedback loops between urban development and economic competitiveness, social cohesion, and responsive governance, and even environmental sustainability,[64] is reflected in the post-2015 urban policy agenda, as is the assumption that states (still) have the power to make a difference through urban planning. However, closer reading of the fragmented academic material reveals only embryonic understanding of the place of cities across global environmental, economic and social systems, and most effort has been deployed to integrating the various streams of urban research, despite the fact that it is obvious that city managers and national governments have to negotiate complex urban and territorial decision making all the time.[65] What is also clear is that there is as yet little academic understanding of what are the most important messages about how to shift the relationship between urban development and global sustainability.

Making non-linear development decisions that will impact multiple dynamics within the urban system over long time frames is the traditional domain of urban planning – itself an interdisciplinary field. Unsurprisingly, the zero draft of the New Urban Agenda[66] makes clear that there is to be an elevated role for planning in the implementation of the 2030 vision. Here the traditional rationale was to equip professionals to draw from specialist knowledge to arbitrate between conflicting imperatives, selecting the path that most effectively secured the public interest. More recently planning has evolved to put greater emphasis on including not just élite or professional views, but also on securing development outcomes that simultaneously affirm ‘people, planet and prosperity’. In other words, planners are being asked to understand and use ever more detailed science about the impact of choices in their cities and territories. They are also required to make recommendations using participatory and political processes over which they have no technical or scientific control. Improving global, national and local scale research in the field of urban, regional and territorial planning would seem to be an obvious response to the new global policy environment, but it will not be enough, especially in those parts of the world where state capacity and planning expertise is sorely lacking.[67]

Interestingly, the global urban development agenda puts revived faith in the practice of urban and regional planning more than it does any other built environment discipline, but makes little reference to what might be the appropriate knowledge platforms from which the profession should draw in order to achieve sustainable practice. The interplay between what planners might be able to contribute to the 2030 Urban Agenda and that of other domains of urban knowledge (culture, finance, ICT and other technologies) is also vague. While understanding and distilling an ever larger and more specialized body of relevant knowledge in order to inform investment is a specific problem of one profession, albeit the profession that is on the front line of the battle for sustainable global urban practice, the planner’s conundrum highlights more systemic issues for coming to grips with urban complexity. On the one hand, global variation and complexity means there is too much information to be able to speak authoritatively about the interplay between social, economic and ecological drivers of urban transformation as laid out by the post-2015 Agenda. On the other hand there is a paucity of readily accessible and useful urban knowledge from the conventional disciplines (botany, engineering, finance, politics, social policy, etc.) to guide evidence based policy-making and policy critique at the local, national and global scale. In a situation where the multidisciplinary traditions of urban research are unable or unwilling to convene to distil and mediate the messages of their collective production for policy makers for reasons set out above, others will take up this task of reconciling what the evidence suggests – often without regard to the integrity of the use of the concepts or evidence. Given this there is the danger that planning, once a pariah discipline, will once again becomes the panacea for achieving sustainable urban development. For planners there is the danger of elevated expectations and the likelihood that they will be left to deliver sustainable urban development without adequate intellectual support. If the post-2015 vision is too important to be left to the UN, it must surely be too important to be entrusted to a single academic discipline and registered profession – especially one that is so poorly represented in the very regions of the world that will be the post-2015 urban crucible.

(ii) Geographical focus

As noted above, the heavy dependence on planning reform to realise the implementation of the NUA and the 2030 vision is, at best, optimistic. The unfounded faith in the ability of built environment professionals to make all the changes that will ensure urban transformation on their own is especially misplaced in Africa and parts of Asia. One reason for the mismatch of expectation is the overt geographical distortion of the understanding of state capacity that emerges from where urban researchers are themselves are concentrated and the locations where urban growth fosters opportunity for innovation. At the precise moment that academic urban studies is finally becoming aware of the knowledge lacuna that surrounds cities of the global south (see Table 3), the policy community has embraced an apparently contradictory direction and affirmed a universal urban agenda – that no longer ensures a focus on poverty or the development world, but that applies the post-2015 agenda to everyone. The advantage of the universal perspective is that it ensures a focus on poverty and inequality in every city and explores the overall urban dynamics rather than focussing on the household or neighbourhood. The danger is that vulnerable people and places are left behind and that the specificity of African and Asian urban challenges, that are not yet well understood, are brushed aside. The push back from the G77 and the Africans at the Pretoria preparatory meeting for Habitat 3 was designed to maintain a focus on informal settlement upgrading and is just one example of how the NUA and global policy positions will need to be expanded if they are to include the everyday experiences of most city managers in the global south.[68]

In advancing the post-2015 Urban Agenda there is an inevitable tension between prioritizing global commitments and confronting local needs. The general objective of making cities and territories work more sustainably appears not to distinguish (at least directly) between the urban imperatives of rich and poor nations, cities in post socialist or social democracies, large or small cities and so on, despite the obvious point that the detail of the challenges faced are likely to be highly differentiated. For issues of mitigation and dematerialization, the policy and scientific interest is derived primarily from aggregating the outcomes of sustainable management or low growth across all cities. A major challenge for urban studies is to ensure that debates about how to make cities work better are aggregated globally, ensuring that greatest global effort is directed at those cities where improved governance is most needed, rather than investing disproportionately in refining the workings of already well-run urban places. A universal agenda should enhance, not detract, from the reorientation of urban studies away from Europe and North America to focus on the key sites of urban transformation in Africa, Latin America and Asia.

Future research associated with the 2030 vision can help negotiate the most problematic aspects of the universality of the 2030 Urban Agenda by focussing on global meta-trends in urban development. First, there is an imperative of generating a far more robust evidence base that accurately draws from cities of all sizes and does not privilege the analysis of trends found in well-researched contexts. Second, the issue of if there is a universal urban condition or not requires much greater interrogation – not just as a hypothetical question, but to ensure that policy recommendations (such as that made in the SGDs for the push for renewable energy or National Urban Policies) are sensitively embedded everywhere. If the sort of large-scale synthesis of urban change is to be representative it will need active geographical reorientation This is not easy, data in poor and understudied places is not easy to get, research is expensive and does not draw on a foundation of quality secondary material, the size of the research groups is limited and getting robust debate started is not simple, especially when extended primary research is required. High impact research is typically synthetic and not foundational, and there are many reasons – aside from expensive and arduous travel – that universities and funding councils hold back from pushing the urban research frontier away from more lucrative areas of immediate self-interest. Yet, without massively improved urban management, we are doomed to unsustainable development.

(iii) Research-led teaching and professional accreditation

Alongside and in tandem with the pure research issues identified above of building a more integrated trans-disciplinary urban studies and fostering a core international scope of work, there is an urgent imperative to transform the curricula of the built environment professionals to enable more appropriate sustainable development interventions, especially in the global south. More and better-qualified built environment graduates (planners, engineers, scientists, architects, finance, public health) are imperative to meeting the aspirations of urban transition. There is an additional teaching dimension to the role of scholarship in shifting policy and practice that is well understood but consistently overlooked, and this is about updating the criteria for certifying built environment professionals. If accreditation and certification are not based on relevant transformative knowledge, the 2030 Urban Agenda will surely stumble.[69]

4. Conclusions

In international policy terms this really is an age of global urbanism. Between 2015 and 2016 key multilateral processes opened up a critical window to integrate a developmental focus on cities as a core driver of sustainability, articulating a universal consensus that makes how cities are run everybody’s business. Agreement on the centrality of ‘the urban’ presupposes, naively, that there is clarity on what the priority international, national and local policy changes should be and that the research required to underpin these claims and effective implementation strategies exists.