Nature-based Urban Living Lab as a catalyst for the circular economy in South Africa

In this blog Dr Kevin Winter describes how the WASTE FEW ULL (Waste Food-Energy-Water Urban Living Labs – Mapping and Reducing Waste in the Food-Energy-Water Nexus) project is supporting improved water use in South Africa through the circular economy.

The problem of untreated surface water runoff

Surface water drainage systems in informal settlements in South Africa, and elsewhere, usually consist of unplanned channels that are used for discharging dirty water that flow alongside makeshift housing structures in highly populated dense settlements (<250 people / km2). The combination of uncontrolled drainage pathways and the extent of the contaminated greywater cause an immediate public health risk to these living spaces, but this is followed by the deterioration in the receiving waters often with irreversible impacts on aquatic life, biodiversity and loss of ecological services. In South Africa, progress in addressing these problems has been extremely slow. The tragedy is that resources are lost in what is accepted as waste products including the loss of resources that could have been contained and recovered from contaminated water, e.g. nutrients. Solving these kinds of problems requires an extraordinary investment and human capacity, but the task is often left up to local authorities who are already overwhelmed with other pressing priorities. In desperation the authorities often intervene with ‘end of pipe’ solutions that involve costly engineering designs and infrastructure that are inappropriate solutions. Cities are growing and local authorities are struggling to keep up with the growing demand for water and sanitation services. Currently about 63% of the population of 55 million are living in urban settlements, but by 2030 the urban population is set to swell to 70%. This is a context that is also deeply rooted in historical legacies that are now being played out in social conflict, contested land and ultimately a failure to achieve many Sustainable Development Goals.

Low cost water treatment without the addition of chemicals

Nature-based processes and solutions have been used in water treatment for centuries although scientific and technical knowledge is still limited. New challenges are testing old ways of managing water treatment. For instance, conventional waste water systems were designed to treat a known array of physical, biological and chemical contaminants, but new compounds and micro-pollutants are entering sewage systems, undetected and untreated. Similar contaminates are found in surface water that is discharged from an informal settlement and this too finds its way into water bodies and water courses without any treatment. The impact, often irrevocable, has led researchers to examine low cost, low energy alternative treatment systems that use green infrastructure and nature-based processes.

The Water Hub is a research initiative that is introducing and testing nature-based solutions. The site is situated in Franschhoek, approximately 85 km north east of Cape Town. Thus far the research has achieved some success in using large biofiltration cells that are designed to polish, clean and filter over 5,000 litres of water daily. Each cell is filled with different natural media such as carbon sources (peach stones), and small and large diameter stone aggregates. Over the past two years the results show that between 75% and 99% of bacteria, nitrogen and phosphate are contained, absorbed or removed by microbes, plants and bacteria. The work at the Water Hub has focused attention on understanding these natural processes and in understanding optimal retention time in these cells and using real-time monitoring sensors and loggers to regulate the flow and volume of water that passes through each cell. Once treated, the water is used for irrigating edible crops. These crops and soils are regularly tested to determine the concentration and levels of nutrients, heavy metals and bacteria.

South Africa is a water scarce country in which water quality and availability are crucial for supporting the development of society and the economy. Without the assurance of water there is little prospect of achieving the SDGs, especially in eradicating hunger and poverty. Arguably addressing the developmental agenda in South Africa begins with water.

The circular economy: integrating food, energy, water and waste

A Circular Economy (CE) aims to close the loop on material and energy flows by turning from linear and wasteful practices to cyclical, restorative, reproductive and smart physical flow structures. The reality is that a CE is much more difficult to achieve, is largely untested and misunderstood. It is possible that is what is needed most to shift CE from ideology to practise is a range of pragmatic tools will enable institutional strategies and policies to accelerate CE, for instance, in incorporating the nexus of Food-Energy-Water-Waste in economic systems; to demonstrate the business case for sustainable nexus management and policy initiatives; to identify the most effective levers for behaviour change; and to understand what kinds of incentives or circumstances will allow individuals and businesses to meaningfully include the urban poor into local economies.

The SUGI WASTEFEW ULL project is composed of four “Urban Living Labs” (ULLs) each with a common aim of reducing waste in their unique urban environments (located in the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, South Africa and Brazil respectively). The project is explores how people create new interactive networks and organize themselves with the intention of reducing waste that are situated in very different biophysical and sociological contexts.

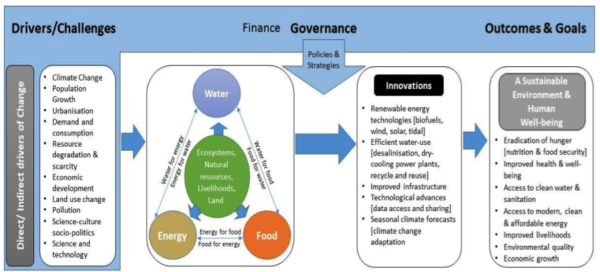

In the case of South Africa, the Water Hub ULL is motivated by at set of critical challenges that are driven by a range of pressing issues such as climate change, urbanisation, poverty, land use change and pollution. These drivers are listed in Figure 1 below. Nexus thinking forces the researchers who are involved in the ULL to work within a systems approach, e.g. measuring and monitoring resource flows; testing new innovations that recognise processes and are not exclusively about the development of market oriented products. The nexus has potential to be one of the most powerful organising frameworks for re-adjusting and disrupting linear economies by introducing policies and strategies that are deliberately directed at achieving sustainable environments and human well-being.

The Water Hub ULL has successfully demonstrated the use of nature-based processes in treating contaminated surface water runoff and to use this water to safely irrigate edible crops. The next stage is to involve local residents from the informal settlement in expanding into various forms of the food production. The goal is to consider establishing a cooperative business enterprise that will managed the sale of vegetables to the local market. The market in turn will generate its own organic waste which will be returned to the Water Hub for recovering energy and producing compost for regenerating the soil. The challenge is to demonstrate how, or if, a CE can become an inclusive and robust system that is capable of impacted the lives of the urban poor.

Permaculture gardens at the Water Hub where spinach, lettuce, beetroot, shards and nasturtium plants each play a complementary role in the growth cycle. Duckweed compost pits in the centre of the garden infuse the soil with nutrients, iron and vitamins.

Permaculture gardens at the Water Hub where spinach, lettuce, beetroot, shards and nasturtium plants each play a complementary role in the growth cycle. Duckweed compost pits in the centre of the garden infuse the soil with nutrients, iron and vitamins.What we are learning

The project started with the treatment of dirty water. After nearly two years of experimentation and tests, the researchers have now learnt how to manage a nature-based system that brings water to a particular quality and can be safely used for irrigating vegetables. New discoveries are showing how nature-based solutions are capable of treating a large volume of water and that it is possible to treat water without the addition of chemicals. The Urban Living Lab aims to advance this research further with plans to extend the research to address other forms of resource recovery. However the most desirable outcome is a strong partnership with local residents in establishing and sustaining a social enterprise that will enable the urban poor to unlock the levers that prevent them from participating in dominant market systems that fail to incorporate a circular economy approach.

References

Mabhaudhi T., Simpson G., Badenhorst J., Mohammed M., Motongera T., Senzanje A. and Jewitt A. 2018 Assessing the State of the Water-Energy-Food (WEF) Nexus in South Africa WRC Report No KV 365/18