Human mobility spreads COVID-19. But whose mobility?

This blog by Qiujie Shi and Tao Liu unpacks some of the connections between the COVID-19 pandemic and migration – and highlights the importance of whose mobility has played the most predominant role in its spread, with more affluent tourists and business people rather than domestic migrants serving as the primary vectors. This is reposted from the PEAK Urban website.

At the time we first encountered it, it was hard to imagine that COVID-19 would become a pandemic barely two months later. At that time, news and social media messages simply attributed the spread of the virus in China to the coincidence with the Chinese Spring Festival, a time when millions of internal migrants return home. At that time, we did not expect that other countries would follow China’s path. After all, the Spring Festival travel period, or chunyun in Chinese, is only specific to China, at a specific time in a year.

But now the epicentre of COVID-19 has now shifted from China to Europe. Italy is now losing more lives on a daily basis than China ever experienced since the outbreak. However, if we take a closer look at the spread of COVID-19 and the geography of migration in China, this development should not come as a surprise.

The spread of COVID-19 in China: are internal migrants to be blamed?

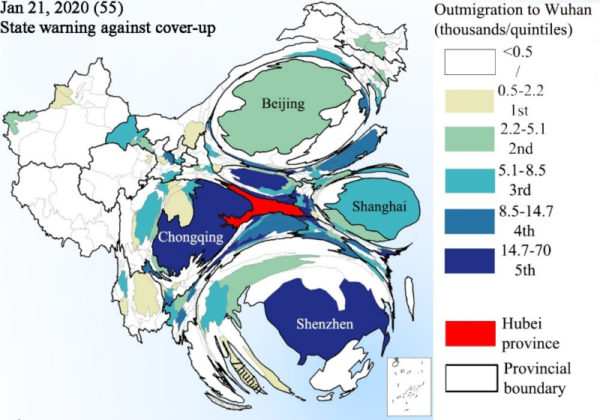

Let us go back to 21 January this year. COVID-19 had already spread beyond Hubei Province, the origin of the outbreak. The number of confirmed cases outside Hubei Province had reached 55. Although by that time most migrants had returned to their hometowns, cities being most affected were not those with large migration to Wuhan, the capital city of Hubei Province. Instead, national leading mega cities, such as Beijing and Shanghai, had the highest confirmed cases (Figure 1). These cities are more connected with Wuhan in business and tourism than in domestic migration. It is very likely that people who first helped the spread of the virus are not the internal migrants, but those who travel frequently for business and tourism.

The contribution of tourism to the COVID-19 spread can be seen more clearly if we compare its geographical distribution of the SARS outbreak in China 17 years ago. For example, SARS never reached Hainan province, a holiday island in China comparable to Mallorca in Spain. But this time many COVID-19 cases have been found there even before the Chinese Spring Festival.

Likewise, picturesque but remote provinces such as Yunnan, Xinjiang and Qinghai were free from SARS, but they are not from COVID-19. In spreading COVID-19, tourists, who move much more frequently and over longer distance than labour migrants, could be critical vectors.

Internal migrants are generally quite heterogeneous. It is true that Wenzhou, a coastal city in China, has the largest number of confirmed cases outside Hubei Province, primarily because the city has a large number of migrants. But most of these are entrepreneurs. While most labour migrants travel annually during the Chinese Spring Festival, business-people mix with different social groups and move around the country frequently, thus are more likely to contribute to the spread of the virus.

From China to Europe: is the virus after the rich?

In Europe, the worst-hit places so far are either so-called global cities with intensive business connections worldwide or are famous tourist destinations.

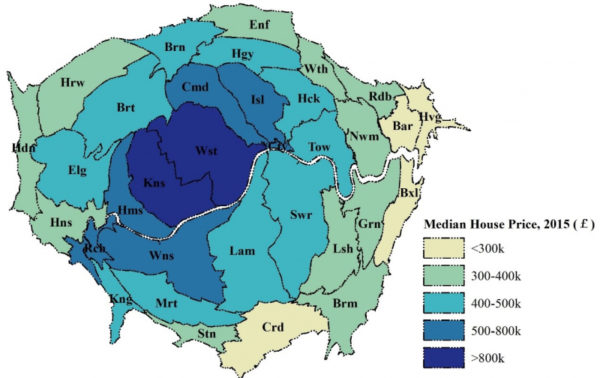

In Italy, Milan is the financial and economic capital; Venice is the world famous tourist destination; and both have recorded extremely large number of Covid-19 cases. In the UK, the leading global city London has the largest number of confirmed cases, followed by the economically prosperous South East region. Within London, Southwark, Westminster, Lambeth, Wandsworth, and Kensington and Chelsea, all gentrified boroughs, are the top five in terms of the number of COVID -19 cases (Figure 2).

There seems to be a pattern here: the richer and more prosperous the place, the more connected it is with the rest of the world, and the more likely it is hit more severely by COVID-19.

The virus itself does not have a preference for specific locations; but travellers who may carry the virus do. Over the past 15 years, global air traffic has increased by 137 percent. But the increase is not evenly distributed. Prosperous places such as Milan, Barcelona, Paris, and London are connected more closely with each other; whereas periphery places are ever more marginalised. Some people can have a conference in Singapore, then go skiing in France, and then return back to their hometowns within one week. Others don’t even hold a passport. Being infected by COVID-19 is possible for everyone; but being highly mobile is not.

When city after city is being locked down, it is perhaps the time to rethink whether all the trips that we have become accustomed to making in the past decade are essential. It is also a time for us to reflect on whether the happiness of our life really depends on so many travels.