Supporting South African Urban Futures: Learning from the Cities Support Programme

South Africa faces a critical urban challenge. This challenge includes the unfinished business of confronting the unequal legacies of the ‘apartheid city’, which divided people according to income and race, and generally promoted distorted development trajectories. South Africa’s urban future is also informed by new pressures. The nature and scale of urban growth – driven by the urban impacts of global economic transformation, technological shifts, climate change, and general insecurity – provide a fragile context for the multi-scale governance reform that we need to make cities more equal, resilient, and productive.

The imperative and opportunity of urban transformation is not unique to South Africa. Globally, the importance of cities and urbanisation in driving sustainable and equitable forms of development is now acknowledged. Moreover, the urgency of devolution and strengthening local governments to secure this developmental role is recognised in multilateral conventions like the Sustainable Development Goals, the New Urban Agenda, and the Paris Agreement. These accords speak to a new global recognition that for cities and city governments to realise their potential as drivers of sustainable development they require particular kinds of innovations, investments, and management interventions.

The recognition that cities hold the key to so many different aspects of a sustainable future is driving reform across various sectors, scales, and actors. Many reform efforts aim to make local or city governments work better within their overall institutional and governance contexts. Here key mechanisms include various forms of national support and innovation programmes; sometimes these are styled as ‘national urban policies’. These kinds of mechanisms, which aim to leverage large-scale changes in the way that cities are run, reflect a cross-government concern to build the power and effectiveness of city governance.

The South African Cities Support Programme

In 2011, the Cities Support Programme (CSP) was set up within the National Treasury of South Africa, a country often seen as a global policy innovator. It was conceived as an intergovernmental platform for urban support and reform to address South Africa’s national urban challenge in the core metropolitan areas, and to promote inclusive, sustainable, and productive modes of urban and economic growth. Through CSP, the National Treasury has sought to promote the spatial transformation of large South African cities from their current fragmented, exclusive, and low-density forms into more compact and integrated places.

A forthcoming book, Supporting City Futures: The Cities Support Programme and the Urban Challenge in South Africa, written as part of the PEAK Urban project by a team based at the African Centre for Cities, seeks to capture the emergence, experiences, and lessons of CSP as a particular – imperfect, yet significant and innovative – approach to urban support and reform. Our intention in writing this book was not only to document the specifics of CSP, but also to capture a larger story about the evolution of urban policy and practice in South Africa. It is a story of a new era of strategic governance, planning, and urban transformation that holds relevance to other countries both in Africa and across the globe.

Where does CSP work?

CSP works with metropolitan municipalities, national departments, provincial governments and other stakeholders to facilitate faster and more inclusive urban economic growth. It focuses its activities on South Africa’s eight ‘metropolitan municipalities’ or ‘metros’, namely Buffalo City, City of Cape Town, City of Johannesburg, City of Tshwane, Ekurhuleni, eThekwini, Mangaung and Nelson Mandela Bay.

The metros are responsible for governing South Africa’s largest and most populated urban areas – places that contribute the greatest portion of economic value to the national fiscus. Yet they face specific and acute challenges of socio-economic and spatial inequality, unsustainable resource use, and ecological damage. At the same time, relative to other municipalities, the metros have the most elaborate and capacitated institutional systems to deliver services to local populations, and to raise local revenue. It follows that they have different kinds of support requirements and regulatory needs.

How does CSP work?

CSP’s is a strategy that recognises and affirms the fiscal, institutional, and political agency of the metros to shape their own developmental trajectories. CSP is about supporting the largely devolved government of cities to perform, rather than dictating the terms of their actions. It is about making cities more capacitated and self-reliant.

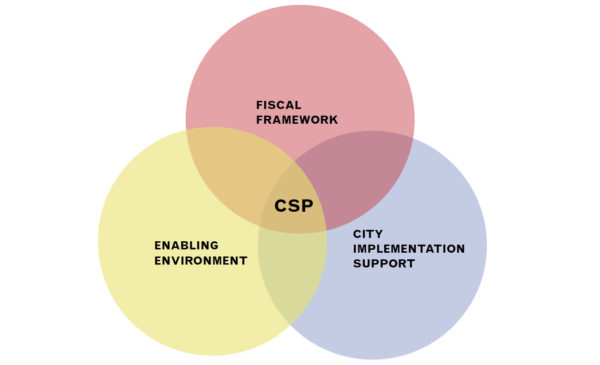

CSP has worked according to the assumption that for cities to reach their full development potential three key areas of work are required. Each cuts across a range of traditional built environment sectors or functions. CSP has focused its activities on the points where the following work areas intersect:

-

-

- Helping to provide a strong fiscal framework to ensure that public resources are managed efficiently and allocated strategically, including through the introduction of greater performance incentives into the system of intergovernmental grants to reward integrated planning and development;

- Creating an enabling intergovernmental environment for city transformation through policy and regulatory reforms, including the devolution of key built environment management functions to the municipal level; and

- Providing an integrated programme of city implementation support, which includes specialised technical assistance, peer learning opportunities, and collaborative performance reviews.

-

Arguably it is the manner in which CSP has sought to provide a platform for the interplay of activities and partnerships at multiple levels, and in multiple domains of governance – the systemic nature of its activities – that sets its strategic and interventive approach apart from other support and reform initiatives in South African history.

Key findings

Our research on CSP uncovered some key lessons that are of relevance to future initiatives of national urban reform, both in South Africa and globally. Some of these lessons are briefly outlined below.

Learning

Over the years since its inception, the CSP team has been forced to learn and adapt with the challenges they have encountered. Our book highlights some of the key lessons learnt during that time. It shows that operating sub-nationally from an institutional base in National Treasury has pros and cons. Likewise, working with an ‘outsourced’ model – employing a small core team and relying on external consultants for most work outputs – can be both beneficial and problematic. CSP has had to adjust and refine itself on the move, and the team has consciously sought to learn from and respond to their emerging experiences. These experiences demonstrate the importance of self-evaluation, and of incorporating feedback mechanisms into ongoing planning and implementation of support activities.

Leading reform through practice

Over time, CSP has developed a strategic approach that aims to influence policy from a practice-led perspective. Rather than acting as a policy think tank or lobbying organisation, dedicated to researching and drafting new policy documents and building political support across state departments, it has sought to gain political traction by introducing new practices. CSP has understood that wider policy change and support can flow from practical reforms and their effects ‘on the ground’ in terms of creating new precedents and building alliances of committed actors and institutions. Real change in the behaviour of municipalities can be realised through the introduction of specific tools and practices – like a new municipal infrastructure grant, a new kind of performance-based plan, or a tool for measuring the fiscal impacts of municipal investment decisions.

One size does not fit all

While there are clear differences in scale and capacity between the metros and other kinds of settlements and local governments, the metros themselves also differ substantially from one another in terms of their land area, population size, economic productivity, poverty rates, revenue, and institutional capacity. Given these variations, from an early stage CSP resolved to take a differentiated approach to working within and between the metros – an approach that has sought to align CSP’s support interventions with existing levels of capacity within each city. Allocating one core team member to each metro has allowed CSP to better understand and respond to local dynamics, to ensure a consistent channel of communication between national and local government, and to help coordinate the full range of its support activities in that city.

Technical capacity alone is not enough

CSP’s experiences highlight the importance of technical capacity and competency as a keystone of urban governance and better kinds of urban development. Yet they also show that technical interventions alone are insufficient – better planning and project implementation, no matter how competent and efficient, will not automatically produce better outcomes in cities. Technical interventions therefore have to be accompanied by and framed within wider processes of systemic reform. Some of these processes relate to human systems: the actual people constituting urban governments and their behaviours. For example, building local leadership capacity to drive ambitious visions and projects of urban transformation is critical. Yet figuring out how to optimally calibrate technical interventions with more systemic and ‘soft’ reforms is challenging. It takes time and effort; it calls for experimentation, occasional failure, reflection, and readjustment.

Balancing institutional rigour and flexibility

To carry out intergovernmental reform effectively, CSP had to be located within the state and had to engage with a variety of state structures. At the same time, as an entity designed to drive systemic change, CSP could not take the typical form of an initiative or institution of the state. It has had to engage across governmental systems often characterised by very different logics, priorities, and strategies relating to cities and urbanisation.

Devising CSP as an intergovernmental ‘platform’ for reform has enabled it to operate with a rare degree of flexibility. This has been particularly important in a fluid and contested political context like that of South Africa. Indeed, the experiences of CSP underscore the importance of understanding the local urban context; of being flexible; of maintaining an open-ended yet strategic outlook; and of navigating the contradictions of politics, policy, and practice rather than simply being normative and prescriptive. They speak, also, to the need for close engagement with city governments, for listening to and understanding their particular challenges and dilemmas, but without losing sight of the need for top-down regulation and support.

One of the key insights emerging from our book is the inherent tension that underpins the creation and operation of a platform like CSP. That is: the balance between ensuring programmatic rigour, on one hand, and maintaining flexibility and responsiveness to context, on the other. Flexibility can be good, but can also raise risks for institutional sustainability. In retrospect, CSP has to some extent been able to ensure an appropriate balance, although the real test will be whether or not South African cities can decisively shift their governance and development trajectories towards more productive, sustainable, and inclusive forms.

The future for urban reform

The story of CSP is one of imperfect experimentation and learning, successes and failures. The question of whether CSP has taken the most appropriate and effective approach to city support and urban reform remains for future research to answer. That answer will be based on the real outcomes and changes that we see in South African cities. Regardless, the stories of big, bold and nationally-supported urban reform initiatives like CSP cannot be overstated, especially as the African continent becomes increasingly urban.

As cities become the focus of policy debate, urban reformers, practitioners, researchers, and students must interrogate the processes as well as the outcomes of urban transformation; ongoing innovation must emerge from the lessons of the past and present.

The PEAK Urban framework provides a productive way of assessing the different kinds of knowledge, methods, and practices that have been, and should be, brought to bear on urban processes in an effort to make them more inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable.