Planning a Better Future for South Africa’s Cities

In this blog post, Lauren Andres and Stuart Denoon-Stevens describe the findings of the South African Planning Education Research (SAPER) project and some of its key implications for the future of South African cities.

The SAPER project started in early 2017 with an initial focus on the curriculum and teaching methods used in urban and spatial planning education. Since then, the project’s scope has widened, specifically bringing in a focus on understanding the needs and challenges of planning practitioners in South Africa, and what implications this has for planning education, before and after graduation.

From 2017 to late 2018, the emphasis of this project was on data collection. In 2017, we undertook a survey with 219 planning practitioners across the country, with questions ranging from concerns relating to work satisfaction, to rank the usefulness of planning competencies learned in planning accredited courses. Supplementing this survey, we also analyzed the race and gender profile of registered professional planners in order to chart the changing demographics of planning in South Africa. In 2018, we undertook 89 interviews with planners across the country, in both metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas. These interviews focused on taking the survey findings further, with the intent being to create a rich picture of the diversity of planning practice. These interviews reflected on issues ranging from the relevance of planning education, to the day to day challenges of planning practice in South Africa.

Some of the key themes this project has tackled include the role of power relations in planning, success and failure of planning reform post-apartheid, development control, challenges for young graduates and issues around professional continuous developments, alternatives and temporary forms of planning and severe resource discrepancies between major urban centres and the rest of the country.

In our investigation of power relations in planning in South Africa, we use the notion of Michel de Certeau’s notion of lieu propre for making sense of how practicing planners respond to power dynamics within municipalities. Through this work, we demonstrate that the strategies of the powerful are themselves subject to negotiation. Planners are not simply passive recipients of legislation and policy, but rather, state strategies are a produced through co-construction between powerful actors, whose interests often are at odds with each other.

In looking at the successes and failures of planning in South Africa, planners’ optimism around the reform of planning legislation in South Africa is noted. However, many frustrations have also been identified, ranging from concerns that plans are being written but not implemented, political interference in planning matters, job reservation, and concerns over capacity in municipalities to undertake planning work. This research is critical of this stance, arguing that many of these concerns could also be interpreted as indicators of a planning system whose design requires a level of competence and capacity unlikely ever to exist. Given this, suggestions are being made that planning reform needs to focus on creating a leaner planning system. The bulk of this reform needs to focus on the land use management system, given that this is both one of the most powerful tools that planners have, as well as the least reformed part of the South African planning system.

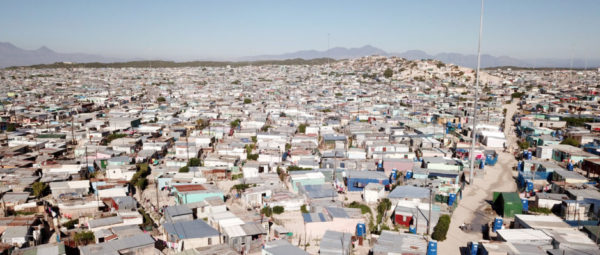

In terms of development control, this project also identifies that planners struggle to conceive of development control tools that go beyond zoning, and more often than not, Euclidean zoning. It is argued that conventional zoning, as practiced in South Africa, is purely suited to respond to the complexity that defines South African settlements, especially concerning informality. In response to this, we draw upon Stefano Moroni and his colleagues’ work on simple rules. This argument is premised on the notion that planning regulations should allow for a diversity of responses, enabling households to easily adapt to changing social, cultural and economic systems.

Looking at alternative forms of planning and temporary uses of urban spaces, we note the difficulty for planners to embrace with adaptability and join up two complex forms of making and shaping spaces, the formal and planned one and the more informal, temporary, diverse and fluctuant one responding to everyday needs and coping. We highlight the difficulty in tackling such temporal dynamics in planning education and then in practice, where planners often lose scope and understanding of what is happening in the field and specifically in the more informal communities.

Finally, reflecting on gaps and need in training, we question the ways in which can be addressed the difficulties for young planners to find a job coupled with resource scarcity faced by the smallest and more rural municipalities. This allows us to raise a range of questions related to places where planning and specific tasks of planning are delivered by non-planners or by planners who don’t have full knowledge, capacities nor resources to tackle challenges they are tasked to address. We argue here that indeed this issue is not specific to South Africa, which despite a severe shortage of planners is still much better placed than most African countries.

Reflecting on the implications of these arguments, we suggest that there should be greater emphasis in planning education on how to negotiate and work within the structures of power, everyday temporalities and find ways to gain additional training once in the field. These findings also emphasise the need for planning educators to teach planning students to be creative, so as to enable planners to be able to think beyond tried and tested methods and approaches to planning, and identify and embrace alternative practices to planning and regulation that are better suited to the South African context. The heart of this is recognizing that planning is a profession with a balance of hard and soft skills, and that competence in both is required in order to be successful as a planner. To quote one of our respondents,

“Walking that line between planning fundamentally being about whom, because that who you plan for, that’s who implements your plans, who approves your plans, who funds your plans, who commissions your plans. That’s all people. And the more technical aspect of the discipline understanding the complex network of by-laws. Understanding hard physical limits like flood mains and soil conditions and dolomite. … Because if you a technical expert but you have no social skills. You not going to get anything on the ground. …If you socially very fluent but can’t put together a good technical plan, you gonna get things on the ground but they gonna be lousy. …: So, constantly working as a person between the troubled past and a less troubled future, between a technically determined profession and a socially fluent phenomenon.”