Creative Experiments in Cities Can Lead to New Jobs and Sustainable Infrastructures

This piece by Liza Rose Cirolia was reposted from the PEAK Urban website and is an edited version of a Commentary originally posted as The Infrastructural Dimensions of African Urbanization.

Gaps in infrastructure systems have long histories in Africa. Decades of underinvestment in urban systems may be the most obvious cause, but it’s not been the only constraint. The complexity of the challenge of financing and developing infrastructure and providing services in African cities requires fundamentally different models of city-building. It requires going beyond the ‘networked infrastructure ideal’ which has underpinned so much of the thinking of what good infrastructure is in cities, and considering (and even proposing) new ways that infrastructure could be delivered, managed and maintained.

Gaps in infrastructure systems have long histories in Africa. Decades of underinvestment in urban systems may be the most obvious cause, but it’s not been the only constraint. The complexity of the challenge of financing and developing infrastructure and providing services in African cities requires fundamentally different models of city-building. It requires going beyond the ‘networked infrastructure ideal’ which has underpinned so much of the thinking of what good infrastructure is in cities, and considering (and even proposing) new ways that infrastructure could be delivered, managed and maintained.

Decentralized urban infrastructure system need to be designed and tested

Centralized infrastructure is a mainstay of the classic infrastructure ideal. However this standardisation has overlooked the potential of decentralized designs which are smaller scale, more locally embedded, and have the potential for incremental extension and transformation. We need to draw upon more inspiring examples found in waste collection, water distribution, and sanitation management, where small-scale provision schemes allow for this potential.

The question of work in African cities is vital

The current fixation with new export and trade zones overlooks the potential of the burgeoning and ever-changing urban fabric to provide meaningful work opportunities for people.

Similarly, the fixation with capital investment as a driver of economic development fails to take into account the importance of labour (and the likely impossibility of the accessing the sorts of capital required to meet the demand). Labour intensive, rather than capital intensive, infrastructure and service provision is necessary in African cities where both work opportunities and capital is limited. Labour intensively should be integrated along the full supply chain of the urban infrastructure, including in the operations and management of these services.

While the current focus on the Smart City may be over-hyped, the importance of the rise of cell phone and internet access and usage on the continent is not. There is a clear need to consider digitally innovative models of service delivery. As mobile technology becomes cheaper, and the tech savvy demographics that make up the ‘youth bulge’ become the primary consumers of urban infrastructure, there are infinite possibilities – many of which will come from local enterprises. Ride hailing apps, mobile payment systems, and service accountability tools (the latter reviewed in this study) – already in use in African cities – utilize lower tech, but digitally creative systems, and have huge potential to improve service provision as well as access and accountability.

Conventional infrastructure delivery models have had a heavy footprint on the planet. Many of these older infrastructural models are increasingly seen as climate risky and older technologies and materials are becoming obsolete. Decentralized and labour-intensive technologies have the potential to gear African cities towards more ecologically sustainable models – for example recycling, grey water reuse, new building materials, and solar panels.

Could we see more of this kind of innovation in Cape Town?

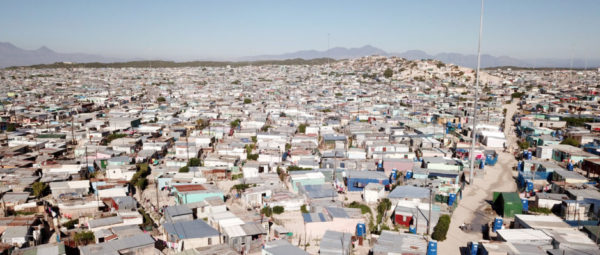

The history of Apartheid spatial planning policy and post-apartheid developmental reforms are unique to South Africa. High levels of fiscal and political decentralization and large-scale programmes for housing and service delivery in South African cities generally, and Cape Town particularly, provide a very different scaffolding both for how we understand infrastructural and financial need and the possibilities which exist for change.

Cape Town has a relatively large budget to cover infrastructure and services but there still huge backlogs in service delivery and infrastructure, in particular in Black and Coloured areas of the city. The failure to allocate sufficient budget to these areas reflects the complex balancing act which the City plays between investing in high rate- paying areas (to maintain the revenue flows to the city) and redressing the apartheid legacy of uneven development in the city.

Addressing the ecological unsustainability of contemporary infrastructure models, experienced more recently in the drought which hit the city is critical. Conventional delivery models are not able to adequately address the challenges which climate change will pose for the city. At the same time, the issue of jobs is fundamental. There is a huge need for work opportunities which are localized and meaningful yet contribute to these climate change innovations. This argument was recently made in the Western Cape Government’s Living Cape policy which made the case for developing labour intensive infrastructure in new development areas of the city.

While Africa’s alarmist urban infrastructure finance gap remains a relevant rallying call to consider the scale and extent of the problem, the next step is to engage in creative experiments in cities – with communities, city governments, and small-scale operators – which enable more labour intensive, innovative, and sustainable systems and networks of delivery.