The self-organising civil society

The SELFCITY Project introduces a new mode of collective governance and societal transition in the face of climate change. This piece, by Professor Eberhard Rothfuß, Dr. Thomas Dörfler and Professor Rob Atkinson, outlines the main findings from their research. This is article will be published in a forthcoming volume of Pan European Networks.

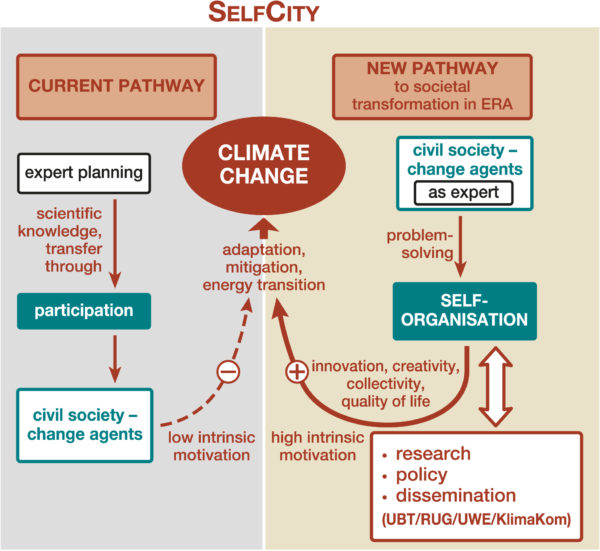

The arena of locally embedded and engendered responses to climate change offers a fruitful and challenging context in which to scrutinise the encounters between established forms of governance and knowledge as they become entwined with locally generated forms of self-organisation. The issue of climate change – which in the global north has largely been dominated by state and market-based responses and associated forms of governance – is an arena in which self-organised local groups have developed initiatives to address the local implications and impacts of climate change.

Drawing on comparative research, the SELFCITY Project (www.selfcity-project.com) investigates how place-based forms of self-organisation relate to existing forms of governance, knowledge production and localised action. Based on case studies by self-organising local groups in Germany, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, and addressing sustainability and climate change, the project investigates a range of responses to climate change that exhibit different levels and forms of ‘organisation’, collaboration and ways of interfacing with more established forms of governance.

Background

We are not arguing that state-led approaches to address ‘global issues’ have become obsolete, as climate change initiatives have shown. For instance, since the Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit of 1992, (inter-)national top-down approaches to global ecological problems (such as CO2 emissions, fuel consumption, global warming, etc.) have been developed through the use of state forms of regulation/incentives and market-based incentives. However, these had tended not to engage with local communities. Even at the level of cities initiatives have often been ‘elite-led’ and failed to engage with and mobilise citizens. Thus, these approaches and their associated forms of governance have their limitations when it comes to the local implications and ecological problems for communities and citizens searching for more immediate changes in lifestyles, and to develop alternative, more sustainable and less exploitative solutions to pressing everyday issues such as nutrition, energy consumption or waste handling.

The SELFCITY Project has found evidence that the flourishing of self-organising initiatives such as sustainable energy and food supply is a reaction to the perceived limitations of market or state-driven approaches to climate change politics. We investigated a diverse collection of ‘green’ initiatives that developed in different contexts, ranging from a ‘transition town’, a ‘transition house’, two energy co-operatives, a free café, a climate change group and an ecological garden. All, however, met our working definition of self- organisation and were seeking to develop locally relevant ways to address climate change, all whilst practicing a sustainable lifestyle. This is why those involved not only came together to develop initiatives, but to become an active part of locally organised activities to address climate change.

From participatory governance to self-organisation

The concept of governance represents a way of organising social action through vertical, horizontal and co-operative mechanisms in contrast to more traditional bureaucratic/hierarchical and market- based forms. A central question is ‘How does self-organisation relate to governance?’ Self-organisation as a means of action ‘from below’ emphasises interaction and discussion between participants, leading to the identification of relevant local issues and the formation of accompanying problem definitions that may challenge, subvert or augment existing governance forms. It offers alternative ways of ‘doing things’ and, potentially, new ways of ‘governing from below’, reflecting local contexts and their understandings of practical problems.

For SELFCITY, knowledge is crucial. It is concerned with the processes of understanding, the development and enhancement of capacities to act, and decision-making procedures. This also involves comparisons and assessment of forms of action, as well as judgements and values in relation to these assessments. Knowledge is always related to social processes of communicative interpretation, which has as its objective the development of a shared understanding of how to enhance the capacity to ‘do things’ in a sustainable and climate friendly manner. Increasingly, the literature has recognised a variety of forms of knowledge, ranging from the scientific and professional to the everyday and local.

However, what counts as knowledge, and its use, is not neutral and value-free. This places constraints on knowledge production and how knowledge is, selectively, used (or not used). Within particular situations actors ‘mobilise’ their knowledge and the knowledge they deem to be relevant for them in selecting a particular course of action to achieve a desired outcome in a particular context. Self- organising approaches tend to favour more local, practical, everyday forms of knowledge and courses of action which are more concrete, effective and relevant to local situations.

Understanding the motivations for local collective action

Based on our research, we found a variety of different, often overlapping reasons why people came together in self-organising ways:

- Constructing a sense of ‘togetherness’, which is a value of its own for most of the initiatives.

- Creating a ‘sense of place’ therefore plays a central role for a majority of the studied initiatives:

- Local knowledge generated by everyday experiences, and by ‘learning by doing’, are considered more appropriate to the issues of (local) climate change and sustainable lifestyles than other forms of knowledge;

- Many are experimenting with practices that aim to secure or enable autonomy in the longer term. For instance, members of an agricultural group aimed to exist independently of the agro- business system. Moreover, working together and communicating between each other was seen as a positive outcome in itself;

- ‘Doing sustainability’ is more important for the practices of many groups – they are primarily orientated towards doing things. Although this does not rule out reflecting on what they have done and ‘how they can do it better’; and

- They seek to discover new ways of ‘governing themselves’ that are relevant to local communities through a ’deliberative’ trial and error process. Moreover, they value a form of governance that is collaborative, non-hierarchical and inclusive.

Policy-relevant findings

- Many groups viewed current climate change policies as abstract or too ‘far away’ from their practical everyday experiences to be of use to them;

- Whilst not simply rejecting scientific knowledge on climate change, a greater emphasis was placed on developing knowledge forms anchored in and relevant to local produce – i.e. that produced through people’s everyday experiences and understanding of how climate change impacts locally;

- In our sample the more organised and professionalised groups tended to have a clearer, arguably more hierarchical organisational structure and a focus on achieving particular tasks. They were less concerned with creating alternative ways of living; rather, they sought to develop particular niches (e.g. local energy generation as an alternative to monopoly suppliers);

- Many groups did realise the need for them to change and develop a vision for their future development, but required some outside support to achieve this;

- Most groups were also aware that they tended to talk to ‘like- minded’ people and wished to engage with the wider community and find ways to involve them in ‘climate friendly activities’ that could be incorporated into their everyday lives. Again outside support could help them do this; and

- A number of groups wished to network with other groups, initially at the local level and then perhaps more widely. Outside support about how to do this was also seen as desirable.

This piece was originally featured in volume 25 of Pan European Network’s Science & Technology.