Satellite Mapping, Big Data and the Politics of Space at the Margins of the Indian City

This blog by Professor Sanjay Srivastava, Professor of Sociology at the Institute of Economic Growth, Delhi University and now part of the project Learning from Small Cities: Governing Imagined Futures and the Dynamics of Change in India’s Smart Urban Age, discusses some of the findings of his previous research in this blog, reposted from the Learning from Small Cities website. All images are the author’s.

Is technology the silver bullet that will both solve the variety of problems that relate to rapid urbanisation in India? Will it lead to a more transparent system of urban governance? Massive changes in urban life in India – including population shifts, infrastructure projects, real estate developments – have led to equally robust responses regarding the best ways of dealing with such change.

However, no matter what else government officials, policy makers and a variety of commentators might suggest, there is one constant theme: that the intensive deployment of technology can overcome social, political and economic complexities that make urbanisation in the Global South such an intractable process.

My project explores relationships between GIS technologies, Big Data processes and urban social life. Using Delhi as template, the project investigates discourses and practices of urban governance as they connect with notions of technologically-driven urban futures. It explores relationships between official visions of the city as expressed through satellite mapping and Big Data and those of the urban poor who reside in the ‘Unauthorised Colonies’ (UCs) of Delhi. The state produces satellite maps and utilises other technologies in order to develop ‘transparent’ and ‘accurate’ urban policies, particularly in relation slum and shanty town localities.

The social dimension of technology and urban planning in the Global South is a largely un-explored topic. It is, however, an indispensable context for exploring ideas of inclusive urbanism. In India, for example, the government’s 100 Smart Cities Mission – based on ‘smart technologies’ – has received unprecedented public funding, as well as being acclaimed as a harbinger of positive urban change. However, according to some commentators, the Mission might also end up producing exclusionary zones of affluence. My project seeks to evaluate the role of technology-as-urban-policy through accounting for the social and political contexts of its operation.

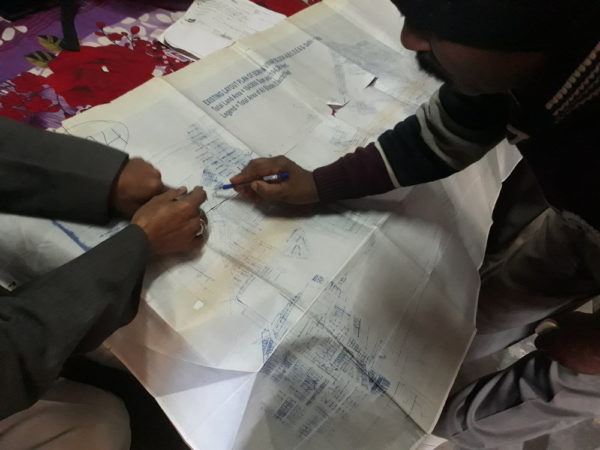

I focus upon the locality of Sonia Vihar, an Unauthorised Colony (UC) located on the banks of the Yamuna river in north-east Delhi. Every now and then, the Delhi government announces ‘regularization’ plans for UCs. The process requires that the Residents Welfare Association (RWA) of an UC supply a map of its locality to the Department of Urban Development to indicate the area it seeks to regularize. This map is then submitted by the Urban Development department to another government entity that deals with satellite mapping. This body is required to ‘verify’ RWA claims through producing satellite maps of the locality.

Between the ‘raw’ map submitted by the RWA to the Urban Development department and the satellite map prepared by the Delhi government lies a complex social domain that has much to tell us about the role of the state, technological imaginations of the city and everyday contestations born out of life at the margins of the cities of the Global South. This is a rich field of investigation regarding ideas of ‘transparent’ governance through satellite mapping and Big Data on the one hand, and local notions of community and claims to the city, on the other. In Sonia Vihar, for example, the satellite maps produced by the government are frequently disputed by residents who claim that the former seeks to deny their claims to the city through rejecting (and redrawing) maps produced by the RWAs. Satellite mapping does not account for the wide range of stakeholders whose actions produce the everyday politics of urban space. These include local landlords and migrant workers who purchase land from them in UCs, land mafias, local politicians, consultants and technology companies.

The project is driven by the following research questions:

1) How do post-colonial nation-states seek to ‘ramp-up’ urban planning through intensive deployment of technology?

2) How do bureaucracies deploy Big Data discourses to produce governance ecosystems and how does this relate to ideas of ‘governmentality’?

3) Do official techno-intensive discourses produce an exclusionary politics of infrastructure?

4) What is the relationship between urbanism as an experiential fact – relating to the materiality of bodies and quotidian social processes – and technological visions of the city?

5) Who are the key promoters of Big Data urbanism and what are their stakes in the process?

6) What can ethnographies of GIS processes and the localities they map tell us about how technologies are experienced and contested? What is the city that emerges through such contests?