Newcastle City Futures: The whirlwind experience of trying to innovate a city

The UKRI/Innovate UK urban living partnership (ULP) pilot for Newcastle and Gateshead ended on 31 January 2018 after an 18-month pilot.

As discussed in my previous blog, ‘Stories from the academy: Newcastle City Futures‘, the ULP, operating under the guise of Newcastle University’s pre-existing ‘Newcastle City Futures’ (NCF) initiative, was established as a collaborative and innovation platform to address urban needs, linking academic research expertise to external partners in the public, private and voluntary sectors, while also facilitating new innovation proof of concept projects. The cross cutting themes of the ULP were engagement, visualisation and digital enablement.

The ULP was an unorthodox research project, focusing on outward partnerships and systems thinking, but was a true pilot – the first ever research project that was jointly owned by all seven research councils and Innovate UK, the first to require multi-disciplinary and multi-sector working under the ethos of co-production, and the first to target a specific place. We not only had to find ways to link together neighbouring academies, Newcastle University and Northumbria University, but also two neighbouring local authorities, Newcastle City Council and Gateshead Council, set within a region that is known to have its occasional internal rivalry.

So what did the ULP funding allow us to achieve in a relatively short space of time? Over the last two years, NCF developed its ULP partnerships from 20 to over 180 organisations: 80 per cent of the partners are businesses. But, critically, the NCF team also committed a considerable amount of time to develop a spirit of partnership and trust across sectors, to encourage joint working and platforms for the creation of innovative ideas and developments. That spirit of partnership and ethos has also extended within universities across 12 different academic schools, linking social science to arts and humanities, science and technology, and medicine. So NCF became something of a mechanism of convenience for the university and its partners, in a space between public, private and community sectors, and between disciplines, a valuable commodity when the gap between agencies and academies can seem to be unbridgeable.

NCF facilitated over 50 project ideas and the establishment of consortia on projects initiated by partner agencies, and has – to date – contributed to the levering in of £10m to Newcastle and Gateshead since August 2016. We covered: digitally enabled homes for an ageing society; accessible designs for new metro trains; digital retailing and vibrant city centres; digital planning tools; creative arts platforms for children; health and wellbeing options for city parks; the design of safe refuges for people with addictions; a community digital health hub; and even a project to design a new street sweeping machine for community use. Some projects were initiated from scratch; others have benefited from NCF scaling up the ambition to create the possibility of funding. Most are ‘smart and socially inclusive’, address urban living needs of communities but applying our expertise in digital and technology; all the projects are multi-sectored, some have focused on new engagement tools, others have been live student projects.

This range of activities developed incrementally in unexpected but workable ways. NCF consciously did not follow a traditional higher education linear path of research idea > funded project > analysis and outcomes > dissemination > impact, but rather a much more agile approach that can be characterised as project idea > partnership building > innovation development > funding opportunity > research project. Very little of the £10m has gone to the university to date, but the 50 projects are sufficiently mature to be transformed into blue chip research bids in the medium term for the university with pre-defined cross-sectoral partners, ready-made test bed evidence, a suite of innovative research methods, multi-disciplinary research teams, clear pathways to impact, and with research, policy, and technological innovation built-in. They are also 50 research impact case studies in waiting.

NCF also developed the diagnostic and research elements. It supported Northumbria University’s virtual reality platform and fly-through model of the city, including acting as a sponsor of their recent AHRC grant success in Memoryscapes (that is also linked to the future of Northumberland Street Area project). We committed funding to enable Newcastle University’s Digital Institute to produce a series of data visualisation maps of Newcastle and Gateshead covering such areas as air pollution, metro use, cultural house accessibility, and walking routes, and these atlas outputs will continue to be worked on in 2018.

We did not set out to develop Newcastle as a smart city, but we have become more immersed into debates about how to make smart cities more visible and meaningful for citizens and businesses. NCF, with the School of Computing Science’s Urban Observatory and the National Innovation Centre for Smart Data, have undoubtedly established Newcastle as a UK pioneer in smart city development, an achievement that was recognised in NCF being awarded the Huawei’s 2017 Smart City Index Education Award. The key to this approach has been to develop a citizen-centric approach that directly engages citizens to co-design projects that will truly enhance city living. The strong partnership between the university, the city council and other key stakeholders has also proved to be crucial.

We changed the governance processes of both Newcastle and Gateshead Councils with new ways of addressing and regulating innovation installations and multi-sector projects across the city. We commissioned a new systems thinking and procurement report for the city council that will guide them into assessing the value of their public realm assets for smart solutions and installations by digital and tech companies. This report, written by Urban Foresight, will also be of use to both universities and partners across the region in promoting their products and services ‘at home’ in a city increasingly known to be a test bed city of innovation.

We have also commissioned Third Life Economics to produce a review report of NCF as an urban living partnership, and they are currently interviewing partners to assess what we did right, what we did wrong, and what models can be drawn from the experience that might be useful for other universities and cities nationally and globally.

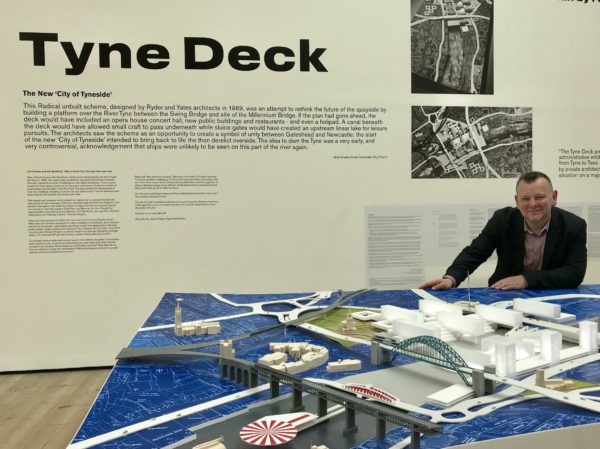

We also funded the establishment of a new crowdfunding platform with Spacehive, ‘TynesideCrowd’, with initial financial support for projects from both local authorities and the university, that will allow communities, the voluntary sector, businesses, and students to suggest new small scale innovation installations relating to digital, arts and culture, health, wellbeing, sustainability, youth, leisure, etc across the region. And we have been active in supporting and delivering the Great Exhibition of the North in Newcastle and Gateshead from June to September 2018 through bespoke projects funded in part from the ULP, including a theatre and performance production called Self Build Utopias for Northern Stage, a new architectural exhibition Idea of North and a new digital game JigsAudio for the Baltic Contemporary Art Gallery, a schools project for Little Inventors about what the city might be like in 2030, and a pop-up exhibition Future Homes for Newcastle Helix.

We will continue to work with partners to try and deliver some of the remaining projects, and support partner agencies in their activities, including the city council’s Connected Cities initiative, Gateshead’s digital and planning initiative, and both universities’ work on data, digital, ageing and energy.

The ULP does not mark the end of Newcastle City Futures. NCF will continue into 2019 with modest funding. We have projects; we also have 180 enthusiastic partners. It would be foolish for us, or indeed the university, to simply drop these following the end of the ULP funding, now that the trust and collaborative spirit has been created.

The team is already fielding a considerable amount of interest from other universities at home and overseas, and from media outlets, to learn more about the ‘Newcastle model’. NCF has proved that it has been a modest broker that can bring about a more joined up world that makes a real difference. What can we all learn from the pilot? Essentially it comes down to finding unique place-based pathways to bring about change:

- Find a suitable ‘opportunity space’ between top-down institutional structures and bottom-up community ideas which can then determine the model and approach, and the degree of success for individual projects;

- Convince your university to establish an intermediate organisation that is sufficiently flexible to enable rapid incubation for non-academic partners’ ideas, as a front door or portal for innovation;

- Be prepared to learn-by-doing, that will include times when you will fail, finding convenient and accessible methods and tools to keep people talking to each other in a co-produced way;

- Don’t start by thinking of research income metrics first and foremost; those opportunities will come on the back of unique partnerships and idea development; this is a medium term game;

- Recognise that you have to sit in a ‘space in-between’ that is both open and suspended in your organisation, and disruptive and provocative for the larger institutions traditionally holding power; there will be a tension between the need for rapid, highly agile working practices and a desire for legitimacy and accountability.

It has been, admittedly, exhausting. We benefited from Newcastle University’s existing commitments to engagement and place and its world-class digital experts, plus NCF’s earlier work as part of the Foresight Future of Cities project. 178 of our 180 partners were a pleasure to work with; two made my life hell, and they just happen to be the two organisations that were critical to shaping ULP activities. But it required significant perseverance to come through the more challenging times, and we did. After all, nothing is impossible.

Could I take this opportunity to publicly thank the ‘NCF family’ of Louise Kempton, Yvonne Huebner, Paul Vallance, Paul Cowie, Michelle Duggan and Fiona McCusker for all the hard work they have put in to this initiative and for being so willing and able to take on the sheer scale of unexpected activities that have come about, beyond expectation and duty in some cases.

More details about the project, including its final outputs, are available here. Mark Tewdwr-Jones is Director of Newcastle City Futures and Professor of Town Planning at Newcastle University. Mark.tewdwr-jones@ncl.ac.uk.