Exploring Age-Friendly Cities in the UK and Brazil: The PLACEAGE Project

Population ageing and urbanisation have raised challenges in terms of how we can best design communities to support an ageing population. Urban areas offer potential advantages in supporting older adults to age-in-place including proximity to amenities, access to social and cultural supports and opportunities for civic participation. Yet urban areas in their current form can be hostile environments to age, presenting barriers to accessing urban spaces, and creating feelings of insecurity and vulnerability. Furthermore, social and spatial inequalities within cities and deeply entrenched neighbourhood deprivation have created further challenges for the design of ‘age-friendly cities’ defined as the policies, services and structures that enable older people to ‘age actively’ – that is, live in good security, enjoy good health and continue to participate fully in society.

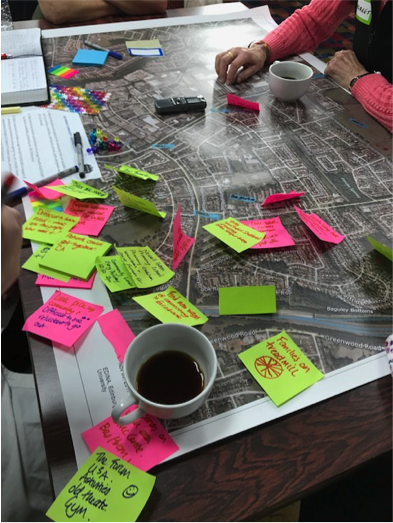

The Place-Making with Older Adults: Towards Age-Friendly Communities (PLACEAGE) project (2016-19) has been conducting research in six cities in the UK (Edinburgh, Glasgow and Manchester) and Brazil (Pelotas, Belo Horizonte and Brasilia) to explore how older adults experience ageing across diverse urban, social and cultural contexts. In year 1, the research collected over 540 surveys, 180 face-to-face semi-structured interviews, 120 walking interviews and 60 photo diaries with older adults living across a total of 18 neighbourhoods in the 6 cities. Neighbourhoods differed according to levels of affluence, distance from the city, and urban density/topography. In year 2, a total of 18 community mapping workshops and 18 workshops were undertaken in the UK and Brazil with over 500 older adults and key stakeholders. Throughout the PLACEAGE project, a community-based participatory research approach has been adopted, with the research team embedding themselves in the local neighbourhood and developing close partnerships with older adults, local community groups, policymakers and practitioners.

The findings from the project have highlighted some of the key issues impacting older adults living in urban communities. For a number of participants, their attachment to the local neighbourhood has been compromised by processes of urban change. Some lower income communities have seen their community erode over time, leading to the closure of local amenities which have had disproportionate impact on older people. Urban regeneration initiatives have brought about significant physical transformation of communities which has challenged how older people move around and connect with their community. Similarly, high population turnover in some areas has undermined feelings of place attachment amongst older adults.

The role of outdoor spaces was a consistent theme across all cities: key barriers to using outdoor space included poor walkability, a lack of sidewalk maintenance, uneven pavements, and few resting points between home and key community services. The lack of bus shelters, inappropriately positioned transport nodes and poor street maintenance (leaves and ice) created further barriers to ‘going out’. Physical hazards also had psycho-social impacts where a number of older adults reported fall incidents which created anxiety when venturing outdoors.

Issues of safety and security were also raised as issues across all neighbourhoods. There was a heightened perception of fear and insecurity when moving around public space. In all cases, this fear often restricted opportunities for community participation, with older people relying upon being accompanied by others when moving around outdoors. In the UK, there was an increased fear of crime in more affluent neighbourhoods. This surprising finding was partly explained by those living in lower income communities reporting feeling part of a tight knit community, where ‘knowing others’ created a perception of security.

Transportation was not always adequate. Older adults expressed difficulties in getting from A to Z and back and again, with provision failing to support a ‘whole journey’ approach. Transport networks up and down main arterial routes were frequent, yet getting ‘across’ communities was complex. Door-to-door transport including community bus services often had eligibility criteria and needed to be booked in advance, preventing spontaneous travel.

In terms of opportunities for social participation, there were a number of activities available for older adults, including arts and crafts and luncheon clubs. These activities were not always fit for purpose and there was a general lack of opportunities for different sub-groups (e.g. the active-old, older men, ethnic minority groups). Positive forms of social participation were generally those that created both a social component and a learning element, whilst being stimulating but not too demanding to participate in. Some reported difficulties in ‘negotiating access’ due to the existence of cliques (pre-established codes and norms) that excluded others.

Knowing what is going in the community was important for older adults to take advantage of local programmes. A number of people were still dependent on traditional forms of communication, e.g. word of mouth or notice boards. Increased dependency on the internet to find out about services excluded those who did not have access, particularly the hard to reach, i.e. those who are frail, and/or experiencing cognitive decline. There was a specific need to target and tailor information in the right ways to older adults.

Green spaces were identified as an important asset in neighbourhoods. An underlying issue was quality vs quantity, with many reporting areas of green space that were unusable – a particular problem in more deprived communities. However, a broad range of green spaces were identified including public parks, private gardens and quasi-public spaces such as community gardens that provided opportunities for restoration, contemplation and social engagement in old age.

Older adults also discussed issues of visibility and invisibility; invisibility for many was defined as a lack of recognition of the skills that they possessed in old age. This was expressed through not being valued, not being respected by others within the community and not having opportunities to help shape their local communities. For example, attempts to bring about local change through civic groups were often thwarted by tokenistic or meaningless forms of consultation at a neighbourhood and city level. Older adults expressed a strong desire to get involved more in the design of age-friendly policy and practice.

Embedded into all stages of the PLACEAGE project have been a series of cross-national visits between the UK and Brazil teams. These visits have enabled opportunities for comparative case study analysis, shared reflections on the research process, and a forum to co-design outputs. A significant emphasis has been placed on communicating findings through local community presentations, a newsletter for the project (https://issuu.com/placeage/docs/final-newsletter-second-edition-2018), twitter account (@placeage) and website (http://placeage.org/en/).

In the final year of the PLACEAGE project we will be designing recommendations and guidelines for the design and development of age-friendly cities in the UK and Brazil, through community and city-level exhibitions and a series of policy mapping workshops with key stakeholders and older adults.