Challenging the gentrification of council estates in London

In this piece Loretta Lees, Principal Investigator of the ESRC-funded project Gentrification, Displacement, and the Impacts of Council Estate Renewal in C21st London, outlines some of the key findings from her project – including data showing that more than 135,000 London council tenants have been displaced since 1997.

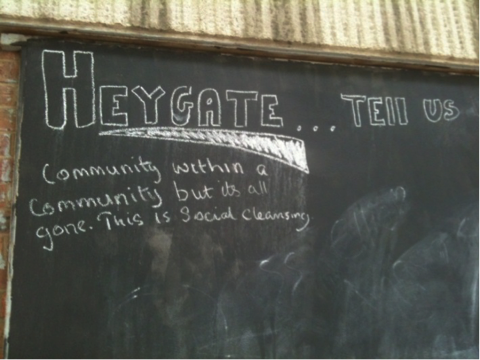

Since being awarded funding for this ESRC project the political mood around the demolition of council estates and their mixed tenure redevelopment through public-private partnerships seems to be changing. Indeed at the 2017 Labour Party conference Jeremy Corbyn finally stood up and criticised the ‘forced gentrification and social cleansing’ of council estates, something that Labour run London boroughs like Haringey and Southwark are at the forefront of. Other Labourites, like David Lammy, who once said that Tottenham could do with a bit of gentrification, has now come out against the Haringey HDV. Indeed, Haringey’s boss Claire Kober, arch advocate for the HDV, has resigned her position in what some see as Labour Party interference in local politics and others a local row about regeneration.

The bigger picture is that since 1997 54,263 units have either been demolished or are slated for demolition on council estates of more than 100 units in London. If we take the London Housing Plan’s average number of people per unit (2.5) a conservative estimate is that 135,658 London council tenants and leaseholders have been or are being displaced. These figures are taken from the database we have collated as part of our ESRC project: this will be updated throughout the duration of the project by our partners, the London Tenants Federation and Just Space. After that, it will be handed over to the GLA.

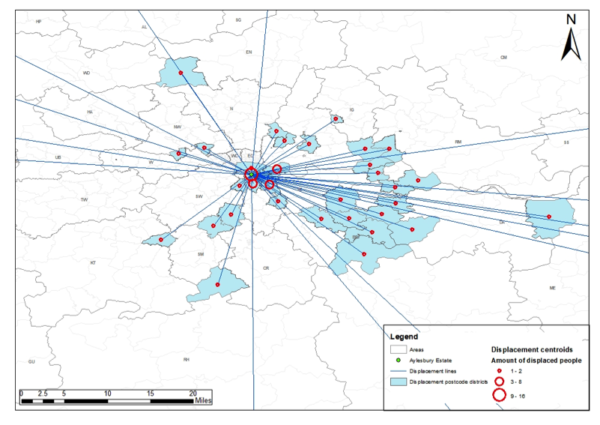

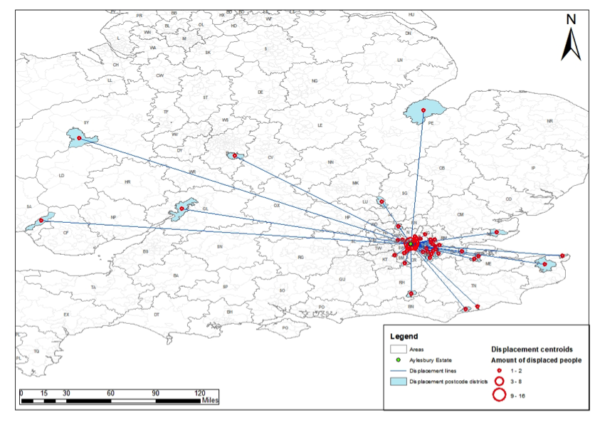

The Heygate Estate in Southwark is now a symbol of the false promises and injustices of this ‘renewal’. More than 3,000 council tenants and leaseholders were displaced, the estate was demolished and its ‘mixed tenure’ replacement, the newly built Elephant Park, marketed off plan in East Asia. The fight for the Aylesbury Estate is on-going (on the first Aylesbury Public Inquiry, see Hubbard and Lees, 2018) and the evidence I gave and was cross examined on at the revised Aylesbury Public Inquiry in January 2018 was drawn from our project. I also presented data on displacement: maps showing where leaseholders from the Aylesbury Estate have ended up, included below.

In addition I included interview material on the impacts of the Aylesbury ‘regeneration’ on council tenants and leaseholders in my witness statement. Two short examples are copied in here:

‘[The new flat] it’s so small, dad can’t get in the bathroom or take a shower. He was in hospital and he’s at my mum’s now…he can’t move here. The kids miss their grandma, they’ve never been in a place where grandma was not there, they will cry at night…’I want to go to Nans’. I’ll say wait until the weekend son. He cries he wants to move back to the Aylesbury. Mum’s losing her marbles, she’s lost so much weight, she lost her friends…one is in Cook Road, one is in Nunhead, she hasn’t seen them since she moved. She hasn’t seen any of them’

Interview with decanted council tenant, BME, aged 35-49, showing break up of families

‘I don’t want to talk about this because the more you talk about it the more you just, stress yourself, and no one is listening to you, and no one is listening and there is nothing they can do. They have made up their minds. They have made up their mind. And no matter what you do, there is nothing you can do… For the past three years, I have been having headaches. And, my life it is just, in the balance. Because you’re not trying to give these children anywhere to settle. And we don’t know what to do, we don’t know your plans. So, almost every month I need to go and get a tablet and on medication. And she was just, they don’t really care. So let’s just end it.’ [wife]

‘It is all, one day I just wake up and I’m swollen here. It is the headache, serious headache, my neck, everyplace. Stress. You don’t know where we are going, when we will get the CPO and they would come and kick you out. Where are you going? You do not know. You see, it is just, sometimes, when I go to the meeting, I am always boiling up, but I just control myself. I just, if they called police, they arrest me, they can arrest me.’ [husband]

Interview with leaseholder couple, BME, aged 60-64, about to receive CPO, showing health impacts and indeed anger.

There are psychological impacts to being decanted from one’s long term home and community. Fullilove (1996) talks about the psychiatric implications of displacement: how the psychological processes of attachment, familiarity and place are threatened by displacement, and the problems of disorientation and alienation that ensue. Our interviews demonstrate this well. Indeed, I have spoken to local GPs who have been disturbed by the public health impacts (eg. stress, anxiety, depression, suicide attempts, etc) with respect to the decanting of the Aylesbury (but they felt that they could not be interviewed due to patient confidentiality). Keene and Geronimus (2011) discuss the same uprooting of low income, urban, BME communities as a result of the HOPE VI program of creating new mixed communities on the site of public housing projects in the US (the model on which British estate renewal into mixed income communities is based: see Lees et al, 2008). They too raise concern about the health impacts on low income communities that already shoulder significant health burdens. In our interviews, these burdens of caring for ill or disabled relatives are evident, as are the escalation of health issues during decantment (see interviews in my witness statement).

Our interviewing is continuing on other estates, like Love Lane in Tottenham and the Carpenters in Newham, helped by the London Tenants Federation and Just Space, our partners on the project. The stories are equally upsetting. The revised Aylesbury Public Inquiry continues in April. We are already in the process of publishing a series of linked papers on displacement: on conceptualising displacement, quantifying it, and qualifying it. The core findings from our research will be presented in an academic monograph down the line, but I have long sought to present my research findings to communities across London. As such we will be publishing an updated version of Staying Put at the close of the project.

In the meantime I continue to present our findings through public speeches and reports, recently at the GLA, the Southwark Tenants AGM, the Haringey Scrutiny Committee, and the ICA. I am also presenting the findings in the US to the Annie E. Casey Foundation later this year in an invited panel meeting on displacement prevention and equitable development strategies. We have been charged with offering recommendations to influence and refine Annie E. Casey’s grant making and investment strategies to reach more equitable community development outcomes across the US. The state-led gentrification of council estates (public housing projects in the US) must be stopped on both sides of the Atlantic. But rejecting this gentrification is only the first step: alternative strategies for maintaining council estates/public housing and building more properly affordable housing need to be developed too. That is work I have begun in other research projects, work that is critically important.

Special thanks to Phil Hubbard (KCL) and Nick Tate (Leicester) CoIs on the project; and Sue Easton (Leicester) and Adam Cooper-Elliot (KCL) RAs on the project, for all their hard work to date.

References

Fullilove, M. (1996) Psychiatric implications of displacement: contributions from the psychology of place, The American Journal of Psychiatry, 153:12:1516-1523.

Hubbard, P. and Lees, L. (2018) The right to community: legal geographies of resistance on London’s final gentrification frontier, CITY (https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2018.1432178).

Keene, D. and Geronimus, A. (2011) Weathering HOPE VI: the importance of evaluating the population health impact of public housing demolition and displacement, Journal of Urban Health, 88:3:417-435.

Lees, L. (2018) Proof of Evidence of Professor Loretta Lees, For the Aylesbury Leaseholders Group Revised Public Inquiry into the London Borough of Southwark (Aylesbury Estate sites 1B-1C), Compulsory Purchase Order 2014, Pins reference: NPCU/CPO/A5840/74092.

Lees, L. (2014) The urban injustices of New Labour’s ‘new urban renewal’: the case of the Aylesbury Estate in London, Antipode, 46:4:921-947.

Lees, L., Slater, T. and Wyly, E. (2008) Gentrification, Routledge: New York.